Posted by Jason Organ in Public science communication

Here we are, once again, at the end of a calendar year filled with lots of exciting news in the field of human evolution. Last year, just as we were finalizing edits on the 2017 Top 5 Human Evolution Discoveries list, the remainder of the skeleton of a human ancestor nown colloquially as “Little Foot” (belonging to the genus Australopithecus, the same genus, but different species, as the famed “Lucy” fossil) was finally revealed after 20

years of cleaning and excavation from its embedding rock. Amazingly, just as we are finishing the edits for this year’s installment of top human evolution discoveries, Little Foot is back in the news. As of the last week of November, full descriptions and analyses of the remainder of the fossils are now available (prior to undergoing peer-review) on the preprint server bioRxiv.

Enjoy reading our Top 6 list for 2018! Why 6? These stories are

too cool not to share.–JMO

By Ella Beaudoin, BA, and Briana Pobiner, PhD, Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution, National Muse \um of Natural History

What does it mean to be human? What makes us unique among all other organisms on Earth? Is it cooperation? Conflict? Creativity? Cognition? There happens to be one anatomical feature that distinguishes modern humans (Homo sapiens) from every other living and extinct animal: our bony chin! But does a feature of our jaws have actual

meaning for our humanity? We want to talk about the top six discoveries of 2018, all from the last 500,000 years of human evolution, that give us more insight into what it means to be human. If you want to learn more about our favorite discoveries from last year, read our 2017 blog post!

1) Migrating modern humans: the oldest modern human fossil found outside of Africa

Every person alive on the planet today is a Homo sapiens,and our species evolved around 300,000 years ago in Africa. In January of this year, a team of archaeologists led by Israel Hershkovitz from Tel Aviv University in Israel made a stunning discovery at a site on the western slope of Mount Carmel in Israel—Misliya Cave. This site had previously yielded

flint artifacts dated to between 140,000 and 250,000 years ago, and the assumption was that these tools were made by Neanderthals which had also occupied Israel at this time.

But tucked in the same layer of sediment as the stone tools was a Homo sapiens upper jaw! Dated to between 177,000 and 194,000 years ago by three different dating techniques, this finding pushes back the evidence for human expansion out of Africa by roughly 40,000 years. It also supports the idea that there were multiple waves of modern humans migrating out of Africa during this time, some of which may not have survived to pass on their genes to modern humans alive today. Remarkably, this jawbone was

discovered by a freshman student at Tel Aviv University working on his firstarchaeological dig in 2002! So, there is hope for students wishing to make a splash in this field!

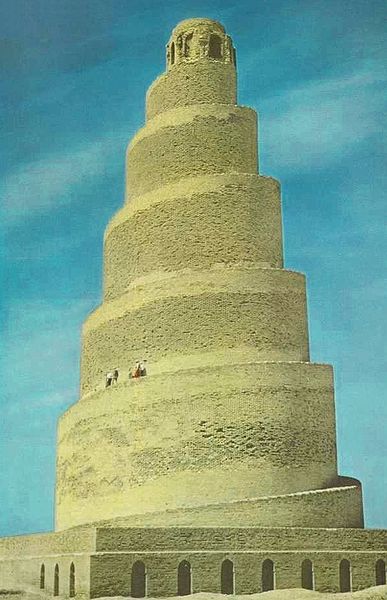

2) Innovating modern humans: long-distance trade, the use of color, and the oldest Middle Stone Age tools in Africa At the prehistoric site of Olorgesailie in southern Kenya, years of careful climate research

and meticulous excavation by a research team lead by Rick Potts of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and Alison Brooks of George Washington University were able to explore both the archaeological and paleoenvironmental records to document behavioral change by modern humans in response to climatic variation. The artifacts show a shift from the larger and clunkier tools of the Acheulean, characterized

by teardrop-shaped handaxes, to the more sophisticated and specialized tools of the Middle Stone Age (MSA). The MSA tools were dated to 320,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of this kind of technology in Africa. They also found evidence that one of the kinds of rock used to make the MSA tools, obsidian, was obtained from at least 55 miles (95 kilometers) away. Such long distances led the teams to conclude that obsidian was traded in social networks, since this is much further than modern human forager groups typically travel in a day. On top of that, the team found red and black rocks (pigments) used for coloring material in the MSA sites, indicating symbolic communication, possibly used to maintain these social networks with distant groups. Finally, all of these innovations occurred during a time of great climate and landscape instability and unpredictability, with a major change in mammal species (about 85%). In the face of this uncertainty, early members of our species seem to have responded by developing technological innovations, greater social connections, and symbolic communication. These exciting findings were published in a set of three papers in Science, focused on the dating of these finds; the stone tool technology and transport and use of pigments; and the

earlier changes in environments and technology that anticipate later characteristics of the stone tools.

(Featured image at the top of this post is the famous “Catwalk Site”, one of the open air displays at the National Museums of Kenya Olorgesailie site museum, which is littered with ~900,000 year old handaxes. Photo courtesy of Briana Pobiner.)

3) Art-making Neanderthals: our close evolutionary cousins actually created the

oldest known cave paintings

Neanderthals are often imagined as primitive brutes dragging clubs behind them. But new

discoveries, including one made last year, continue to reshape that image. A team led by

Alistair Pike from the University of Southampton found red ocher paintings – dots, boxes,

abstract animal figures, and handprints – deep inside three Spanish caves. The most

amazing part? These paintings dated to at least 65,000 years ago –a full 20,000-25,000

years before Homo sapiens arrived in Europe (which was 40,000 to 45,000 years ago)!

The age of the paintings was determined by using uranium-thorium dating of white crusts

made of calcium carbonate that had formed on top of the paintings by water percolating

through the rocks. Since the calcite precipitated on top of the paintings, the paintings

must have been there first – so they are older than the age of the calcite. The age of the

paintings suggests that Neanderthals made them. It has been generally assumed that

symbolic thought (the representation of reality through abstract concepts, such as art) was

a uniquely Homo sapiensability. But sharing our ability for symbolic thought with

Neanderthals means we may have to redraw our images of Neanderthal in popular

culture: forget the club, maybe they should be holding paint brushes instead.

4) Trekking modern humans: the oldest modern human footprints in North

America

When we think about how we make our marks on this world, we often picture leaving

behind cave paintings, structures, old fire pits, and discarded objects. But even a footprint

can leave behind traces of past movement! A discovery this year by a team led by

Duncan McLaran from the University of Victoria with representatives from the Heiltsuk

and Wuikinuxv First Nations revealed the oldest footprints in North America ! These 29

footprints were made by at least three people on the tiny Canadian island of Calvert. The

team used Carbon-14 dating of fossilized wood found in association with the footprints to

date the find to 13,000 years ago. This site may have been a stop on a late Pleistocene

coastal route humans used when migrating from Asia to the Americas. Because of their

small size, some of the footprints must have been made by a child – who would have

worn about a size 7 kids shoe today, if they were wearing shoes (interestingly, the

evidence indicates they were walking barefoot). As humans, our social and caregiving

nature has been essential to our survival. One of the research team members, Jennifer

Walkus, mentioned why the child’s footprints were particularly special: “Because so

often kids are absent from the archeological record. This really makes the archaeology

more personal.” Any site with preserved human footprints is pretty special, as there are

currently only a few dozen in the world.

5) Winter-stressed, nursing Neanderthals: Neanderthal children’s teeth reveal

intimate details of their daily lives

Evidence of children is very rare in the prehistoric archaeological record; their bones are

more delicate than those of adults and therefore less likely to survive and fossilize, and

their material artifacts are also almost impossible to identify. For instance, a stone tool

made by a child might be interpreted as made hastily or by a novice, and toys are quite a

new invention. To find remains that are conclusively juvenile is very exciting to

archaeologists – not only for the personal connection we feel, but for the new insights we

can learn about how individuals grew, flourished, and according to a new study led by

Dr. Tanya Smith from Griffith University in Australia, suffered. Smith and her team

studied the teeth of two Neanderthal children who lived 250,000 years ago in southern

France. They took thin sections of the two teeth and “read” the layers of enamel, which

develops in a way similar to tree rings: in times of stress, slight variations occur in the

layers of tooth enamel. The tooth enamel chemistry also recorded environmental

variation based on the climate where the Neanderthals grew up, because it reflects the

chemistry of the water and the food that the Neanderthals kids ate and drank. The team

determined that the two young Neanderthals were physically stressed during the winter

months – they likely experienced fevers, vitamin deficiency, or disease more often during

the colder seasons. The team found repeated high levels of lead exposure in both

Neanderthal teeth, though the exact source of the lead is unclear – it could have been

from eating or drinking contaminated food or water, or inhaling smoke from a fire made

from contaminated material. They also found that one of the Neanderthals was born in

the spring and weaned in the fall, and nursed until it was about 2.5 years old, similar to

the average age of weaning in non-industrial modern human populations. (Our closest

living relatives (chimpanzees and bonobos) nurse for much longer than we do, up to 5

years.) Discoveries like this are another indication that Neanderthals are more similar to

Homo sapiensthan we had ever thought. Paleoanthropologist Kristin Krueger notes how

discoveries like this are making “the dividing line between ‘them’ and ‘us’ [become more

blurry] every day.”

6) Hybridizing hominins: the first discovery of an ancient human hybrid

Speaking of blurring lines (and probably the biggest story of the year): a new discovery

from Denisova Cave in Siberia has added to the complicated history of Neanderthals and

other ancient human species. While Neanderthal fossils have been known for nearly two

centuries, Denisovans are a population of hominins only discovered in 2008 based on the

sequencing of their genome from a 41,000-year-old finger bone fragment from Denisova

Cave – which was also inhabited by Neanderthals and modern humans (and whom they

also mated with). While all of the known Denisovan fossils could nearly fit in one of your

hands, the amount of information we can gain from their DNA is enormous! This year, a

stunning discovery was made from a fragment of a long bone identified as coming from a

13-year-old girl nicknamed “Denny” who lived about 90,000 years ago: she was the

daughter of a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father . A team led by Viviane Slon and

Svante Pääbo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig,

Germany first looked at her mitochondrial DNA and found that it was Neanderthal – but

that didn’t seem to be her whole genetic story. They then sequenced her nuclear genome

and compared it to the genomes of other Neanderthals and Denisovans from the same

cave, and compared it to a modern human with no Neanderthal ancestry. They found that

about 40% of Denny’s DNA fragments matched a Neanderthal genome, and another 40%

matched a Denisovan genome. The team then realized that this meant she had acquired

one set of chromosomes from each of her parents, who must have been two different

types of early humans. Since her mitochondrial DNA – which is inherited from your

mother – was Neanderthal, the team could say with certainty that her mother was a

Neanderthal and a father that was Denisovan. However, the research team is very careful

about not using the word “hybrid” in their paper, instead stating instead that Denny is a

“first generation person of mixed ancestry.” They note the tenuous nature of the

biological species concept: the idea that one major way to distinguish one species from

another is that individuals of different species cannot mate and produce fertile offspring.

Yet we see interbreeding commonly occurring in the natural world, especially when two

populations seem to be in the early stages of speciating – because speciation is a process

that often takes a long time. It is clear from genetic evidence that Neanderthals and Homo

sapiens individuals were sometimes able to mate and produce children, but it is unclear if

these matings included difficulty with becoming pregnant or bringing a fetus to term –

and modern human females and Neanderthal males may have had particular trouble

making babies . While Neanderthals contributed DNA to the modern human genome, the

reverse seems not to have occurred. Regardless of the complicated history of

intermingling of different early human groups, Dr. Skoglund from the Francis Crick

institute echoes what many other researchers are thinking about this amazing

discovery, “[that Denny might be] the most fascinating person who has had their genome

sequenced.”