On the anniversary of the publication of Machiavelli’s “The Prince”

THE BOOK THAT SHAPED MODERN POLITICS

By Amir Taheri

For over 1500 years, people interested in the political dimension of human existence regarded one book as their ultimate guide to a labyrinthine world that tempted and terrorized them at the same time. The book was Aristotle’s “Politics” that, though originally written as a depiction of political ideals in ancient Greece, appealed to other cultures across centuries and continents. In Europe, Aristotle’s book generated centuries of speculation on and experimentation about the art of government. The Scholastics, notably Saint Thomas Aquinas, used it as a plank in reconciling Christianity with philosophy. Although “Politics” was not fully translated into Arabic and Persian, the two major languages of classical Islam, its partial renditions did inspire numerous treatises on the “behavior of princes” (sirat al-moluk) and the art of good governance in general (Siasatnameh)..

For over 1500 years, people interested in the political dimension of human existence regarded one book as their ultimate guide to a labyrinthine world that tempted and terrorized them at the same time. The book was Aristotle’s “Politics” that, though originally written as a depiction of political ideals in ancient Greece, appealed to other cultures across centuries and continents. In Europe, Aristotle’s book generated centuries of speculation on and experimentation about the art of government. The Scholastics, notably Saint Thomas Aquinas, used it as a plank in reconciling Christianity with philosophy. Although “Politics” was not fully translated into Arabic and Persian, the two major languages of classical Islam, its partial renditions did inspire numerous treatises on the “behavior of princes” (sirat al-moluk) and the art of good governance in general (Siasatnameh)..

However, Aristotle’s masterpiece was a recipe for ideal government in “the most perfect political community” which the First Teacher described as “one in which the middle class is in control, and outnumbers both of the other classes.” That conjecture was not to be reached until the 20th century when the middle classes established their hold on political power in a number of Western societies. But even then, it did not take long before it became clear that middle class or, as Marx would say bourgeois, rule did not necessarily create “the most perfect political community.”

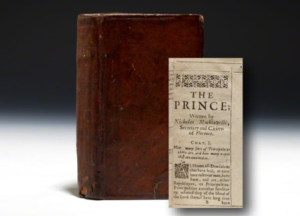

Aristotle had studied the ideal; but what was needed was to examine the real. That was the task that one retired civil servant set for himself in 1513. The man in question was Niccolo Machiavelli who had been imprisoned and forced into exile as a result of one of the frequent regime changes experienced by his native city Florence. Machiavelli’s project shaped up into a slim book, in most editions just over 100 pages, first published under the title “De Principatibus” (On Rulership) in 1513-14.

Thus, the world is now marking the 500th anniversary of Machiavelli’s work with numerous seminars held by universities and research centers in more than 50 countries. The fifth centenary of “The Prince”, as the little book came to be known after its definitive edition appeared in 1532, has also inspired hundreds of books and many more essays. President Barack Obama prides himself in owning a copy as does North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il. “The Prince” is also the bedside book for both Vladimir Putin of Russia and Japanese Premier Shinzo Abe. Over the centuries the term “Machiavellianism” has entered almost every major language often as a synonym for diabolical cunning and absence of principles.

Interest in “The Prince”cuts across ideological barriers.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau regarded the book as a draft for his own social contract.

Voltaire and Diderot regarded “The Prince” as the first major attempt at de-sacralizing political power while David Hume and Adam Smith saw it as a humanist manifesto for a new political system. The English historian Thomas Macaulay read “The Prince” as a recipe for democratic republican government. He wrote: “It is notorious that Machiavelli was, through life, a zealous republican.. We are acquainted with few writings which exhibit so much elevation of sentiment, so pure and warm zeal for public good, so just a view of the duties and rights of citizens, as those of Machiavelli.”

The Founding Fathers of the United States, the first nation-state created as a shareholding company with a constitution, made much wise, though partial, use of Machiavelli’s ideas on government structures and the role of political institutions.

Hegel believed that Machiavelli wrote “The Prince” as a plea for the creation of a powerful state to forge unity among peoples. Fichte, however, presented Machiavelli as an advocate of “nations” at a time that Europe was moving away from the idea of empire towards the concept of nationhood. In 1803 Hegel, disappointed ion his own dreams of German national unity asserted that “Machiavelli’s voice has dies without effect.”

ISLAMIC BENEVOLENT DESPOT

In the 19th century Islamic reformers, among them Jamaleddin al-Afghani, saw “The Prince” as a treatise on the “benevolent despot” they thought was needed to save the people of Islam from poverty, ignorance and decline.

Giuseppe Manzoni, one of the fathers of Italian nationalism, saw “The Prince” as an idealized depiction of what a future Italian state “inspired by God” should look like. However, he missed one crucial point. Manzoni’s God is universal while Machiavelli’s is quintessentially Italian. While Manzoni wanted to enlist God’s support in Italy’s struggle for independence across the board, Machiavelli was satisfied with a divine blessing for what Italians did themselves. ” God is not willing to do everything, and thus take away our free will and that share of glory which belongs to us,” he wrote.

To Hannah Arendt, Machiavelli was “the spiritual father of revolution in the modern sense.” In the 1920s, Bolshevik theoretician Lev Kamenev described”The Prince” as a “zoological study of power in pre-Communist societies.” Benito Mussolini spoke of “my Machiavelli” and claimed the Florentine as the spiritual father of the fascist movement. Mussolini’s compatriot, Antonio Gramsci, however, insisted the Machiavelli’s “The Prince” should be seen as a metaphor for the Communist Party.

Thus, here is a book that has appealed to and intrigued people from across the ideological spectrum. Some like Marx dismissed it as “unscientific while others, like Leo Strauss described it as “a scientific book, because it conveys a general teaching that is based on reasoning .

At any rate, at the start of 2014, Machiavelli’s little book is still top of best-seller lists in the”politics” category not only in the West but also in such unlikely places as China, Japan and Iran.

Most dictionaries define Machiavellianism as “the political theory of Machiavelli; especially: the view that politics is amoral and that any means however unscrupulous can justifiably be used in achieving political power”.

That definition, however, is based on a superficial reading a text that, may be because of its beguiling simplicity, id often unjustifiably densified. Machiavelli regards politics as amoral, not immoral. For him politics is the art of building a solid state that is capable of ensuring the security of tis subjects and/or citizens within the framework of law.

Since none could feel secure without enjoying basic freedoms, it goes without saying that the politics that Machiavelli talks about is not intended to create a tyranny.

Within Machiavelli’s politics, the individual subject or citizen has the choice of being moral or immoral. In fact, it is to Machiavelli’s credit that he denies the state any claim on defining, let alone trying to impose, any form of morality outside the law of the land. To him politics is a neutral, pragmatic means of organizing the affairs of the community in a way that benefits the largest number possible. Though politics and ethics are separate and distinct domains in Machiavelli this does not mean that politics should not be subjected to ethical critique as any other part of the human condition. In fact, the 18th century English theologian Sir Thomas Browne claimed that “The Prince” establishes a political deontology that subjects every ruler to permanent ethical judgment.

GOOD GOVERNANCE AS SCIENCE

Without saying so, Machiavelli treats governance as science and, thus, could be regarded as father of the modern concept of politics as a science rather than an art. Thus the rules of politics, like those of science, are neither moral nor immoral. Take for example, the law of gravity. If you push a tyrant out of a high window, gravity would operate in the same way as if you pushed a loveable grandmother. The chief task of “The Prince” is to ensure the preservation of the state, that is to say maintaining a measure of law and order needed for people to live and work in peace and harmony. Because chaos is the principal enemy, a bad prince that ensures peace and stability should always be preferred to a good one that leads the ship of state into uncertain stormy waters. “The Prince must learn not to be good when necessary,” he states.

But how does the prince achieve the coveted degree of stability? Machiavelli suggests “good armies” and “good laws” as the necessary ingredients for achieving stability. That, in turn, leads him into acknowledging other necessities. There could be no “good armies” without a good economy to support the machinery needed for ensuring law and order. And, could there be “good laws” without their wiling acceptance by a majority of citizens? The answer is: no. But how would that acceptance be assessed? Machiavelli did not imagine democratic elections as they developed four centuries after he wrote his book. What he did, however, was to urge close and systematic consultations through which “The Prince” is informed of the opinions of his subjects. He uses an intriguing term, “riscontro”, a rough equivalent of the German “Zeitgeist”, which means “the spirit of the time or “the mood of the moment.”

At any given time, regardless of laws and traditions there are things that society does not tolerate. For example, in every society there comes a time when the idea of preventing girls from going to school is no longer acceptable. Thus the “Prince” who tries to impose a ban on schooling for girls would run counter to “rioscontro” wit grave consequences for the stability of the state. At the same time, the fact that the “Prince” might want something does not necessarily mean it could or should be undertaken. If it runs against “riscontro” it should be shelved without much ado. A successful “Prince” moves with his time and his people as defined in time, neither faster nor more slowly.

Having made his distinction between ideology and governance, Machiavelli proceeds to depict the political space as separate from that of religion. This does not mean that Machiavelli should be regarded as the father, or at least grandfather, of modern secularism. In his time, the concept did not yet exist. What he does is to understand that religion is the realm of the ideal while politics is that of the real.

Religion is all about certainty while politics is the province of doubt, second-thoughts, U-turns and compromises. Dragging religion into the mud-swamps of politics is bad for both. In religion, man seeks perfection-a perfection forever beyond his reach. This is how Machiavelli describes men who “are ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous, and as long as you succeed they are yours entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and children when the need is far distant: but when it approaches they turn against you. . . . Men have less scruple in offending one who is beloved than one who is feared, for love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of punishment which never fails.”

Here is yet another passage: “One can generally say this about men: they are ungrateful, fickle, simulators and dissimulators, avoiders of dangers and greedy for gain. While you work for their benefit, they are completely yours, offering you their blood, their property, their sons and their lives, when the need to do so is far away. But when the need draws nearer to you, they turn away.”

To many students of Machiavelli that crucial passage is the most glaring example of his cynicism. However, to those familiar with history and the political realities of our societies across the world , the statement has a ring of truth. The statement may be of interest for another reason. It punctures whatever pretense that we might have about achieving perfection by dissolving the real in the ideal. Admitting that we are full of flaws, that we are not perfect, could bless us with a degree of humility without which we cannot live in peace and harmony with our fellow human beings. Machiavelli could not have imagined the type of politics that Western societies were to develop 200 years after him on their way to democratization. Nevertheless, he did imagine what he called “Civil Principality”. In “The Prince” the whole of Chapter IX is devoted to that topic. Machiavelli defines the subject in this way: “When a private citizen becomes Prince of his native city not through intrigue or any other intolerable violence but with the favor of his fellow citizens, this can be called a civil principality, the acquisition of which neither depends completely upon virtue, nor upon fortune, but on a fortunate astuteness.” Machiavelli does not suggest how that “favor of fellow citizens” could be ascertained. But traditional societies, both in Christendom and Islam, developed a number of devices, including act of allegiance and pledges of fealty (bay’ah) that legitimized the new prince. Interestingly, Machiavelli makes it clear that “ a civil principality founded on people’s support is more stable than one founded on aristocratic support.

THE REDEEMER AND NATIONHOOD

It is not only by foreseeing democratic participation, a culture of secularism, and the search for the lowest common denominator that “The Prince” has helped shape the politics in the modern world. Almost 300 years before the very concept of nationalism stared to dominate European, and later, global thought Machiavelli realized that the imperial forms under which diverse communities had been wrought together for over 1500 years were no longer efficient. It would not be far-fetched to regard Machiavelli as the grandfather, if not the father, of modern nationalism. ” I love my fatherland more than my soul,” he wrote. In fact, successive generations of Italians have regarded Machiavelli’s book as a manifesto for Italy’s resurgence (Risorgimento) as a unified nation. “The Prince” ends with an “Exhortation” that is a clarion call for Italians to throw off the foreign yokes under which they live and create a new independent state.

Many readers find the “Exhortation” chapter as an incongruous afterthought to “The Prince”. Throughout the book we are made to understand that the ideal ruler need not be an extraordinary man.

All he needs to achieve success is good sense, temperance, an ability to understand the mood of his time, and readiness to change his words and policies to ensure the stability ad perennity of the state. In “exhortation” , however, Machiavelli seeks a ” Redeemer”, an exceptional heroic figure that Italy, trampled underfoot by bigger powers such as France, Spain, Austria and even Switzerland, needs to unite and re-emerge as an independent nation-state. To be sure, Machiavelli does not quite tell us where his ideal Italy is actually located. He refers to Rome, Tuscany, and the Kingdom of Naples as constituent blocs of his dream Italy. But he makes no reference to Savoy, Sicily, Sardinia and Veneto among other regions. In reality, Italy had never existed as Italy which designates the boot-like peninsula; it had been a patchwork of mini-states based on two dozen cities or had found expression in the Roman Empire stretching across three continents.

Machiavelli’s knowledge of Roman history is, at times, surprisingly approximative. (For example he puts Emperor Commodus after Severus.)

In any case, Machiavelli names only four “ redeemers” in history, men who freed their nations from subjugation and went on to found new states. The four are Moses for Hebrews, Cyrus for Persians, Theseus for the Greeks and Romulus for Romans. Machiavelli’s “Redeemer” is a prophet armed who embarks on a divine mission to create a new world. He is wise, eloquent and humane, in other words, exceptional. In his Opera Nabucco, in 1842, Verdi offered his immortal Va’ Pensero aria of the slaves inspired by Machiavelli’s idea of a “Redeemer”. But Italy did not get a “Redeemer”, even though it did become independent in 1870. It did get caricatures of the “redeemer”, however, in the form of Mussolini’s Il Duce (The Duke), and more recently, Silvio Berlusconi’s Il Condottiere (The Conductor)

Not all nations could have a “Redeemer” all the time. Most mortals must live under an ordinary “Prince”, hoping he has read Machiavelli and learnt a few tips from him.