By David Sibray

By David Sibray

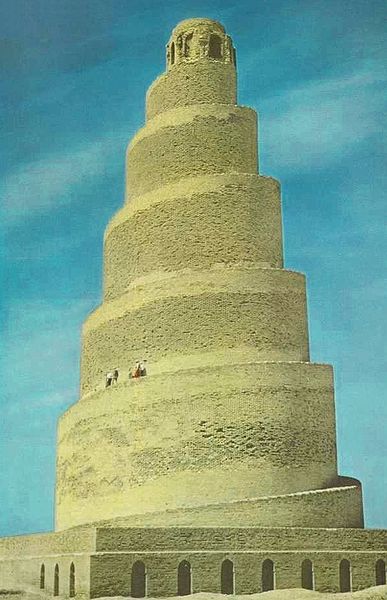

Images of beasts and men decorate a boulder at the Half-Moon archaeological site, now submerged beneath the Ohio River.

When pioneers and other explorers first ventured into what would become West Virginia, they encountered artifacts of a much earlier age — carvings, burial mounds, and stone walls, the origins of which natives could not explain with certainty.

Petroglyphs inscribed in rock and featuring human and animal figures were perhaps the most striking and inexplicable finds. Mounds and earthworks could be practically accounted for as defensive or monumental — but carvings? They were certainly communications.

With whom were the creators attempting to communicate and why? Were the carvings inspired by ritual or sheerly as human expression?

Archaeologists can only speculate. Without written records, we may never know with certainty.

Scholars have, however, begun to piece together the larger story of life here before written record, thanks to artifacts that remain — carvings, earthworks, and common relics such as arrowheads and shards of pottery.

Some of the most extensively carved rocks, we now know, were located in river valleys, along which many prehistoric settlements were located. Most are long gone, though others are protected by archaeologists who will not reveal their locations.

Some have been destroyed and incorporated into new construction. Others were drowned when rivers such as the Ohio, Kanawha, and Monongahela were locked and dammed for navigation. Detail from Half Moon archaeological site showing human and animal figures.

One of the northernmost of these “Ancient Monuments” in West Virginia is now located under water along the Ohio River in the Maryland Heights neighborhood of Weirton, West Virginia.

The Half-Moon Site, as the monument is known today, was surveyed in 1838 by James McBride — long after its discovery by European explorers. His account was published in 1847 in Squier and Davis’s “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley,” which was later reviewed by the Ohio Historical Society, republished in the West Virginia Archaeologist in 1978.

“July 4, 1838. When making a survey of a turnpike road up the Ohio River, on the of the (sic) third of July 1838 in the evening encamped on the farm of Mr. Ephraim Cable four miles above Steubenville. On the next morning July 4th accompanied by John W. Erwin, Civil Enginer (sic), crossed the Ohio river to the Virginia side, for the purpose of examining a rock which we were informed was on that side.”

“We found the rock lying on the Virginia side of the river. It lies about three feet above low water mark, having a flat surface of about nine feet by seven inclining a little toward the water. It is of hard sand stone, and all over the surface are various figures cut and sunk into the hard rock, amongst these figures are rude representations of the human form, tracts (sic) of human feet representing the bare foot and print of the toes as if made in soft mud, tracts of horses, turkeys, and a rabbit. Several figures of snakes, a tortois (sic), and other figures not understood. A drawing of them was made on the spot by Mr. Erwin as here represented.

“There are a number of other rocks lying on the shore both above and below the one on which the figures are cut, which appear as though they had at some former period rolled down from the hill above. Below this rock is one of much larger size, being about twenty feet in diameter, with a flat surface inclining up stream, on which are several deep cuts or the remains of figures, with which the rock may have been covered; but owing to its exposed situation the current of the river, ice and other floating substances have worn the face of the rock and defaced the figures upon it.”

James L. Murphy, of the Ohio Historical Society, noted in his review of McBride’s survey that the sketch of the rock and petroglyphs was likely inaccurate, though that criticism did not devalue the find.

“It seems clear from McBride’s description that Squier and Davis’ drawing is also inaccurate in portraying the petroglyphs as lying on an upright, monument-like slab of sandstone, for McBride clearly states that the rock had a flat surface “inclining a little towards the water.” Probably the other discrepancies between McBride’s drawing and that of Squier and Davis’ are also due to artistic licences or carelessness on the part of the engraver.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Half-Moon rock is only one of many archaeological sites that did and do exist elsewhere in the Ohio Valley near Weirton and elsewhere in West Virginia.

Read also: Geologic anomaly visible only from space; Ghostly rumble tied to underground source

Do you think you’ve found an archaeological site in West Virginia? Many such sites have been cataloged though they’re their locations have not been publicized. In this way archaeologists can help protect them. Such delicate, finite resources are best explored by trained investigators.

If you think you’ve found an archaeological landmark or relic, contact the the W.Va. Division of Culture and History at 304-558-0220.

Interested in supporting or finding out more about archaeology in West Virginia. Contact the West Virginia Archaeological Society or the Council for West Virginia Archaeology.

https://wvexplorer.com/2019/01/12/strange-carvings-greeted-west-virginia-explorers/