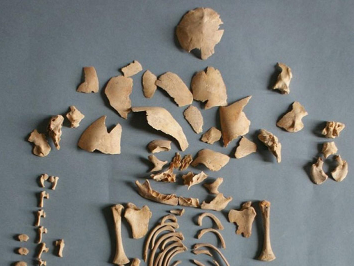

ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA—According to a statement released by the University of Adelaide, statistician Adam “Ben” Rohrlach of the University of Adelaide, Kay Prüfer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and an international team of researchers screened some 10,000 DNA samples taken from human remains dating from the Mesolithic period through the mid-nineteenth century for evidence of autosomal trisomies, or a third copy of one of the first 22 chromosomes in the human genome. The researchers were able to identify six infants with Down syndrome, which occurs when a person carries an extra copy of chromosome 21. “This is the first time we’ve been able to reliably detect cases [of Down syndrome] in ancient remains,” Rohrlach said. The study also identified the remains of a perinatal infant who had Edwards syndrome, a condition caused by three copies of chromosome 18. “These individuals were buried according to either the standard practices of their time or were in some way treated specially,” Rohrlach added. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Nature Communications.

ADELAIDE, AUSTRALIA—According to a statement released by the University of Adelaide, statistician Adam “Ben” Rohrlach of the University of Adelaide, Kay Prüfer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and an international team of researchers screened some 10,000 DNA samples taken from human remains dating from the Mesolithic period through the mid-nineteenth century for evidence of autosomal trisomies, or a third copy of one of the first 22 chromosomes in the human genome. The researchers were able to identify six infants with Down syndrome, which occurs when a person carries an extra copy of chromosome 21. “This is the first time we’ve been able to reliably detect cases [of Down syndrome] in ancient remains,” Rohrlach said. The study also identified the remains of a perinatal infant who had Edwards syndrome, a condition caused by three copies of chromosome 18. “These individuals were buried according to either the standard practices of their time or were in some way treated specially,” Rohrlach added. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Nature Communications.