ATHENS, GREECE—ABC News reports that traces of a round building estimated to be 4,000 years old were discovered on a hilltop on the island of Crete during an investigation conducted ahead of the construction of a radar station to serve a new airport. No other Minoan structures like it have been found, according to archaeologist and Culture Minister Lina Mendoni. The entire structure covers about 19,000 square feet, and consists of eight stepped stone walls measuring up to more than five feet tall surrounding an inner circle split into smaller, interconnecting spaces. Researchers think that these rooms would have been covered by a conical roof, similar to early Minoan beehive tombs. Many animal bones were recovered inside, suggesting that the building may have been used for communal ceremonies and offerings involving the consumption of food and wine. Mendoni said that a new location for the radar station will be found.

ATHENS, GREECE—ABC News reports that traces of a round building estimated to be 4,000 years old were discovered on a hilltop on the island of Crete during an investigation conducted ahead of the construction of a radar station to serve a new airport. No other Minoan structures like it have been found, according to archaeologist and Culture Minister Lina Mendoni. The entire structure covers about 19,000 square feet, and consists of eight stepped stone walls measuring up to more than five feet tall surrounding an inner circle split into smaller, interconnecting spaces. Researchers think that these rooms would have been covered by a conical roof, similar to early Minoan beehive tombs. Many animal bones were recovered inside, suggesting that the building may have been used for communal ceremonies and offerings involving the consumption of food and wine. Mendoni said that a new location for the radar station will be found.

REPUBLIC MEDIEVAL SILVER COINS DISCOVERED IN CZECH

KUTNÁ HORA, CZECH REPUBLIC—According to a Live Science report, a hiker has discovered a hoard of more than 2,150 silver coins in a field in the central Czech Republic. Researchers from the Czech Academy of Sciences identified the coins as medieval versions of the denarius, a standard silver coin minted by the Roman Empire. The coins had been stored in a pottery jar, but only the bottom of it has survived years of plowing. Examination of the coins has shown that they were minted in Prague in the eleventh century during the reigns of the Přemyslid kings Vratislav II, Břetislav II, and Bořivoj II. The coins are thought to have been buried in Bohemia sometime in the first quarter of the twelfth century. “At that time, there were disputes in the country between members of the Přemyslid dynasty over the princely throne in Prague,” said archaeologist Filip Velímský. The scientists plan to analyze the composition of the coins to try to determine the origin of the silver.

KUTNÁ HORA, CZECH REPUBLIC—According to a Live Science report, a hiker has discovered a hoard of more than 2,150 silver coins in a field in the central Czech Republic. Researchers from the Czech Academy of Sciences identified the coins as medieval versions of the denarius, a standard silver coin minted by the Roman Empire. The coins had been stored in a pottery jar, but only the bottom of it has survived years of plowing. Examination of the coins has shown that they were minted in Prague in the eleventh century during the reigns of the Přemyslid kings Vratislav II, Břetislav II, and Bořivoj II. The coins are thought to have been buried in Bohemia sometime in the first quarter of the twelfth century. “At that time, there were disputes in the country between members of the Přemyslid dynasty over the princely throne in Prague,” said archaeologist Filip Velímský. The scientists plan to analyze the composition of the coins to try to determine the origin of the silver.

ARTIFACTS RECOVERED FROM AN ANCIENT WELL IN ROME’S PORT CITY

ROME, ITALY—According to a report in The Art Newspaper, well-preserved pottery, burned animal bones, a wooden chalice or funnel, peach pits, oil lamps, and marble fragments have been recovered from waterlogged soil in an ancient well at the Temple of Hercules in Ostia Antica, the site of ancient Rome’s port at the mouth of the Tiber River. The objects found in the 10-foot-deep shaft have been dated to the first and second centuries B.C. Burn marks on the bones suggest that the animals may have been sacrificed, cooked, and eaten during temple banquets. “These finds are a direct testament of the ritual activity that took place at the sanctuary,” said Alessandro D’Alessio of Ostia Antica Archaeological Park. He thinks that the carved wooden chalice or funnel may have been used as a pipe or musical instrument. “Refined objects like this are rare given that wood usually deteriorates,” D’Alessio explained. The objects will be restored and displayed at the site museum.

ROME, ITALY—According to a report in The Art Newspaper, well-preserved pottery, burned animal bones, a wooden chalice or funnel, peach pits, oil lamps, and marble fragments have been recovered from waterlogged soil in an ancient well at the Temple of Hercules in Ostia Antica, the site of ancient Rome’s port at the mouth of the Tiber River. The objects found in the 10-foot-deep shaft have been dated to the first and second centuries B.C. Burn marks on the bones suggest that the animals may have been sacrificed, cooked, and eaten during temple banquets. “These finds are a direct testament of the ritual activity that took place at the sanctuary,” said Alessandro D’Alessio of Ostia Antica Archaeological Park. He thinks that the carved wooden chalice or funnel may have been used as a pipe or musical instrument. “Refined objects like this are rare given that wood usually deteriorates,” D’Alessio explained. The objects will be restored and displayed at the site museum.

International Day of Plant Health 1 May

Plants are life – we depend on them for 80 percent of the food we eat and 98 percent of the oxygen we breathe. But international travel and trade have been associated with the introduction and spread of plant pests. Invasive pest species are one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss and threaten the delicate web of life that sustains our planet. Pests and diseases have also been associated with rising temperatures which create new niches for pests to populate and spread. In response, the use of pesticides could increase, which harms pollinators, natural pest enemies and organisms crucial for a healthy environment. Protecting plant health is essential by promoting environmentally friendly practices such as integrated pest management. International standards for phytosanitary measures (ISPMs) in trade also help prevent the introduction and spread of plant pests across borders.

International Day of Plant Health 2024: Plant health, safe trade and digital technology

Each year, over 240 million containers move between countries, carrying goods including plant products, posing biosecurity risks. In addition, about 80 percent of international trade consignments include wood packaging material, providing a pathway for pest transmission. As a result, damages from invasive pest species incur global economic losses of approximately USD 220 billion annually. Protecting plant health across borders is essential by promoting global collaboration and international standards, such as the International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs). Innovative solutions like electronic phytosanitary certification (ePhyto) streamline the process, making trade quicker and more secure.

The International Day of Plant Health 2024 calls on everyone to raise awareness and take action to keep our plants healthy and ensure food safety and safe trade for sustainable economies and livelihoods.

https://www.fao.org/plant-health-day/en

Roman Lead Ingots From Spain Studied

CÓRDOBA, SPAIN—According to a statement released by the University of Córdoba, recent analysis of three first-century A.D. lead ingots recovered from southern Spain’s site of Los Escoriales de Doña Rama in the twentieth century suggests that ancient Córdoba, the capital of the Roman region of Baetica, was a center for smelting lead. The Romans used the metal to make spoons, tiles, pipes, and other everyday objects. Each ingot is about 18 inches long, triangular in shape, and weighs more than 50 pounds. One of them is broken in half, and two of them still bear the identification mark, “S S,” for Societas Sisaponensis, a mining company. The mark and the shape of the ingots indicates that they had been intended for export, while chemical analysis of the ingots shows that they came from a mining area that includes the site where they were recovered. “This information demonstrates that, in antiquity, these northern regions of Córdoba boasted major metallurgical networks of great commercial and economic importance in the Mediterranean,” said Antonio Monterroso Checa of the University of Córdoba. He thinks Los Escoriales de Doña Rama may have been the site of a mining town with a foundry, a processing area, and maybe even a fortress.

CÓRDOBA, SPAIN—According to a statement released by the University of Córdoba, recent analysis of three first-century A.D. lead ingots recovered from southern Spain’s site of Los Escoriales de Doña Rama in the twentieth century suggests that ancient Córdoba, the capital of the Roman region of Baetica, was a center for smelting lead. The Romans used the metal to make spoons, tiles, pipes, and other everyday objects. Each ingot is about 18 inches long, triangular in shape, and weighs more than 50 pounds. One of them is broken in half, and two of them still bear the identification mark, “S S,” for Societas Sisaponensis, a mining company. The mark and the shape of the ingots indicates that they had been intended for export, while chemical analysis of the ingots shows that they came from a mining area that includes the site where they were recovered. “This information demonstrates that, in antiquity, these northern regions of Córdoba boasted major metallurgical networks of great commercial and economic importance in the Mediterranean,” said Antonio Monterroso Checa of the University of Córdoba. He thinks Los Escoriales de Doña Rama may have been the site of a mining town with a foundry, a processing area, and maybe even a fortress.

Possible Algonquian Capital Identified in North Carolina

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA—According to an IFL Science report, researchers led by Eric Klingelhofer of the First Colony Foundation have uncovered evidence for a palisade and nine houses at the possible site of an Algonquian village within Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. Explorers Phillip Amadas and Arthur Barlow wrote of their visit to an Algonquian village in 1584, and described it as having “nine houses, built of cedar, and fortified round with sharp trees.” The possible village site was identified last year through Algonquian pottery dated to the sixteenth century, and a ring of copper wire thought to have been made in England that could indicate contact with the English, Klingelhofer explained. The researchers suggest that elite members of the Algonquian community lived within the palisaded walls, and ruled a territory that included present-day Dare County, Roanoke Island, and parts of mainland North Carolina. The rest of the Algonquian population lived outside the walls and raised crops, he concluded. Some scholars think the English colonists who went missing from their settlement at Roanoke may have integrated into this Algonquian community.

DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA—According to an IFL Science report, researchers led by Eric Klingelhofer of the First Colony Foundation have uncovered evidence for a palisade and nine houses at the possible site of an Algonquian village within Fort Raleigh National Historic Site. Explorers Phillip Amadas and Arthur Barlow wrote of their visit to an Algonquian village in 1584, and described it as having “nine houses, built of cedar, and fortified round with sharp trees.” The possible village site was identified last year through Algonquian pottery dated to the sixteenth century, and a ring of copper wire thought to have been made in England that could indicate contact with the English, Klingelhofer explained. The researchers suggest that elite members of the Algonquian community lived within the palisaded walls, and ruled a territory that included present-day Dare County, Roanoke Island, and parts of mainland North Carolina. The rest of the Algonquian population lived outside the walls and raised crops, he concluded. Some scholars think the English colonists who went missing from their settlement at Roanoke may have integrated into this Algonquian community.

Occupation of Cave in Saudi Arabia Dates Back 10,000 Years

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA—Nature News reports that hundreds of human and animal bones and more than 40 fragments of stone tools have been uncovered at the entrance to a lava tube cave in northwestern Saudi Arabia. The stone tools are thought to be as much as 10,000 years old,

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA—Nature News reports that hundreds of human and animal bones and more than 40 fragments of stone tools have been uncovered at the entrance to a lava tube cave in northwestern Saudi Arabia. The stone tools are thought to be as much as 10,000 years old,  while the oldest human bone fragment has been dated to about 7,000 years ago. Zooarchaeologist Mathew Stewart of Griffith University and his colleagues said that the distribution of the artifacts indicates that the cave was occupied intermittently, for short periods. Nearby rock art depicting people with goats and sheep suggests that herders may have come to the cave for rest and shelter while traveling from oasis to oasis across the basalt plain of Harrat Khaybar, as they still do today. These routes have probably been used for thousands of years, explained Melissa Kennedy of the University of Sydney, since 4,500-year-old tombs have been found in the region. “People are very lazy,” she said. “You find the easiest route and you stick to it.” Read the original scholarly article about this research in PLOS ONE.

while the oldest human bone fragment has been dated to about 7,000 years ago. Zooarchaeologist Mathew Stewart of Griffith University and his colleagues said that the distribution of the artifacts indicates that the cave was occupied intermittently, for short periods. Nearby rock art depicting people with goats and sheep suggests that herders may have come to the cave for rest and shelter while traveling from oasis to oasis across the basalt plain of Harrat Khaybar, as they still do today. These routes have probably been used for thousands of years, explained Melissa Kennedy of the University of Sydney, since 4,500-year-old tombs have been found in the region. “People are very lazy,” she said. “You find the easiest route and you stick to it.” Read the original scholarly article about this research in PLOS ONE.

When Mother Earth sends us a message

Mother Earth is clearly urging a call to action. Nature is suffering. Oceans filling with plastic and turning more acidic. Extreme heat, wildfires and floods, have affected millions of people.

Mother Earth is clearly urging a call to action. Nature is suffering. Oceans filling with plastic and turning more acidic. Extreme heat, wildfires and floods, have affected millions of people.

Climate change, man-made changes to nature as well as crimes that disrupt biodiversity, such as deforestation, land-use change, intensified agriculture and livestock production or the growing illegal wildlife trade, can accelerate the speed of destruction of the planet.

This is the third Mother Earth Day celebrated within the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Ecosystems support all life on Earth. The healthier our ecosystems are, the healthier the planet – and its people. Restoring our damaged ecosystems will help to end poverty, combat climate change and prevent mass extinction. But we will only succeed if everyone plays a part.

UNESCO: Takht-e Soleiman

UNESCO: Takht-e Soleiman

The article below on Takht-e Soleyman (or Takht-e Suleiman) is by UNESCO. Kindly note that except one photo, all other images and accompanying captions do not appear in the UNESCO posting.

==========================================================================

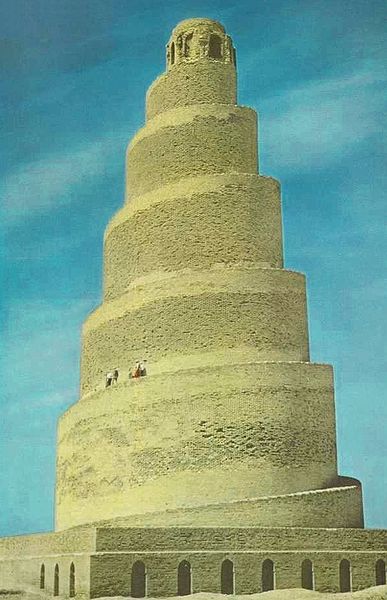

The archaeological site of Takht-e Soleyman, in north-western Iran, is situated in a valley set in a volcanic mountain region. The site includes the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary partly rebuilt in the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period (13th century) as well as a temple of the Sasanian period (6th and 7th centuries) dedicated to Anahita.

One of the structures at Takhte Suleiman (Picture Source: World Historia).

One of the structures at Takhte Suleiman (Picture Source: World Historia).

The site has important symbolic significance. The designs of the fire temple, the palace and the general layout have strongly influenced the development of Islamic architecture.

Brief Synthesis

The archaeological ensemble called Takht-e Soleyman (“Throne of Solomon”) is situated on a remote plain surrounded by mountains in northwestern Iran’s West Azerbaijan province. The site has strong symbolic and spiritual significance related to fire and water – the principal reason for its occupation from ancient times – and stands as an exceptional testimony of the continuation of a cult related to fire and water over a period of some 2,500 years. Located here, in a harmonious composition inspired by its natural setting, are the remains of an exceptional ensemble of royal architecture of Persia’s Sasanian dynasty (3rd to 7th centuries). Integrated with the palatial architecture is an outstanding example of Zoroastrian sanctuary; this composition at Takht-e Soleyman can be considered an important prototype.

An excellent overview of the site of the site of Ādur-Gushnasp or Shiz (modern-day Takhte Suleiman) (Picture Source: Iran Atlas). The Ādur-Gushnasp sacred fire was dedicated to the Arteshtaran (Elite warriors) of the Sassanian Spah (Modern Persian: Sepah = Army).

An excellent overview of the site of the site of Ādur-Gushnasp or Shiz (modern-day Takhte Suleiman) (Picture Source: Iran Atlas). The Ādur-Gushnasp sacred fire was dedicated to the Arteshtaran (Elite warriors) of the Sassanian Spah (Modern Persian: Sepah = Army).

An artesian lake and a volcano are essential elements of Takht-e Soleyman. At the site’s heart is a fortified oval platform rising about 60 metres above the surrounding plain and measuring about 350 m by 550 m. On this platform are an artesian lake, a Zoroastrian fire temple, a temple dedicated to Anahita (the divinity of the waters), and a Sasanian royal sanctuary. This site was destroyed at the end of the Sasanian era, but was revived and partly rebuilt in the 13th century. About three kilometres west is an ancient volcano, Zendan-e Soleyman, which rises about 100 m above its surroundings. At its summit are the remains of shrines and temples dating from the first millennium BC.

Takht-e Soleyman was the principal sanctuary and foremost site of Zoroastrianism, the Sasanian state religion. This early monotheistic faith has had an important influence on Islam and Christianity; likewise, the designs of the fire temple and the royal palace, and the site’s general layout, had a strong influence on the development of religious architecture in the Islamic period, and became a major architectural reference for other cultures in both the East and the West. The site also has many important symbolic relationships, being associated with beliefs much older than Zoroastrianism as well as with significant biblical figures and legends.

The 10-ha property also includes Tepe Majid, an archaeological mound culturally related to Zendan-e Soleyman; the mountain to the east of Takht-e Soleyman that served as quarry for the site; and Belqeis Mountain 7.5 km to the northeast, on which are the remains of a Sasanian-era citadel. The archaeological heritage of the Takht-e Soleyman ensemble is further enriched by the Sasanian town (which has not yet been excavated) located in the 7,438-ha landscape buffer zones.

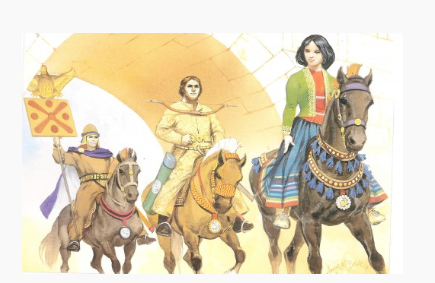

A reconstruction of the late Sassanians at Ādur Gušnasp or Shiz (Takht e Suleiman in Azarbaijan, northwest Iran) by Kaveh Farrokh (painting by the late Angus Mcbride) in Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی–. To the left rides a chief Mobed (a top-ranking Zoroastrain priest or Magus), General Shahrbaraz (lit. “Boar of the realm”) is situated in the center and Queen Boran (Poorandokht) leads to the right.

A reconstruction of the late Sassanians at Ādur Gušnasp or Shiz (Takht e Suleiman in Azarbaijan, northwest Iran) by Kaveh Farrokh (painting by the late Angus Mcbride) in Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی–. To the left rides a chief Mobed (a top-ranking Zoroastrain priest or Magus), General Shahrbaraz (lit. “Boar of the realm”) is situated in the center and Queen Boran (Poorandokht) leads to the right.

Criterion (i):Takht-e Soleyman is an outstanding ensemble of royal architecture, joining the principal architectural elements created by the Sassanians in a harmonious composition inspired by their natural context.

Criterion (ii):The composition and the architectural elements created by the Sassanians at Takht-e Soleyman have had strong influence not only in the development of religious architecture in the Islamic period, but also in other cultures.

Criterion (iii):The ensemble of Takht-e Soleyman is an exceptional testimony of the continuation of cult related to fire and water over a period of some two and half millennia. The archaeological heritage of the site is further enriched by the Sassanian town, which is still to be excavated.

Criterion (iv):Takht-e Soleyman represents an outstanding example of Zoroastrian sanctuary, integrated with Sasanian palatial architecture within a composition, which can be seen as a prototype.

Criterion (vi): As the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary, Takht-e Soleyman is the foremost site associated with one of the early monotheistic religions of the world. The site has many important symbolic relationships, being also a testimony of the association of the ancient beliefs, much earlier than the Zoroastrianism, as well as in its association with significant biblical figures and legends.

Integrity

Within the boundaries of the property are located the known elements and components necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, including the lake and the volcano, archaeological remains related to the Zoroastrian sanctuary, and archaeological remains related to the royal architecture of the Sassanian dynasty. Masonry rooftops have collapsed in some areas, but the configurations and functions of the buildings remain evident.

One of the archways at Ādur-Gushnasp (Picture Source: World Historia).

One of the archways at Ādur-Gushnasp (Picture Source: World Historia).

The region’s climate, particularly the long rainy season and extreme temperature variations, as well as seismic action represent the major threats to the integrity of the original stone and masonry materials. Potential risks in the future include development pressures and the construction of visitor facilities in the buffer zones around the sites. Furthermore, there is potential conflict between the interests of the farmers and archaeologists, particularly in the event that excavations are undertaken in the valley fields.

Authenticity

The Takht-e Soleyman archaeological ensemble is authentic in terms of its forms and design, materials and substance, and location and setting, as well as, to a degree, the use and the spirit of the fire temple. Excavated only recently, the archaeological property’s restorations and reconstructions are relatively limited so far: a section of the outer wall near the southern entrance has been rebuilt, using for the most part original stones recovered from the fallen remains; and part of the brick vaults of the palace structures have been rebuilt using modern brick but in the same pattern as the original. As a whole, these interventions can be seen as necessary, and do not compromise the authenticity of the property, which retains its historic ruin aspect. The ancient fire temple still serves pilgrims performing Zoroastrian ceremonies.

The Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple. After the prayers are concluded, a “Damavaz” (a ceremony participants) holds aloft the censer containing fire and incense in his hand to pass around the congregation. As this is done, the Damavaz repeats the Avesta term “Hamazour” (translation: Let us unite in good deeds). Participants first move their hands over the fire and then over their faces: this symbolizes their ambition to unite in good works and the spread of righteousness (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).

The Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple. After the prayers are concluded, a “Damavaz” (a ceremony participants) holds aloft the censer containing fire and incense in his hand to pass around the congregation. As this is done, the Damavaz repeats the Avesta term “Hamazour” (translation: Let us unite in good deeds). Participants first move their hands over the fire and then over their faces: this symbolizes their ambition to unite in good works and the spread of righteousness (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).

Protection and Management requirements

Takht-e Soleyman was inscribed on the national heritage list of Iran in 1931, and it is subject to legal protection under the Law on the Protection of National Treasures (1930, updated 1998) and the Law of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization Charter (n. 3487-Qaf, 1988). The inscribed World Heritage property, which is owned by the Government of Iran, is under the legal protection and management of the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (which is administered and funded by the Government of Iran). Acting on its behalf, Takht-e Soleyman World Heritage Base is responsible for implementation of the archaeology, conservation, tourism, and education programs, and for site management. These activities are funded by the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization, as well as by occasional international support. The current management plan, prepared in 2010, organizes managerial strategies and activities over a 15-year period.

An excellent view of the edge of the lake at Ādur-Gushnasp (Photo Source: Public Domain).

An excellent view of the edge of the lake at Ādur-Gushnasp (Photo Source: Public Domain).

Sustaining the Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require continuing periodic on-site observations to determine whether the climate or other factors will lead to a negative impact on the Outstanding Universal Value, integrity or authenticity of the property; and employing internationally recognized scientific standards and techniques to properly safeguard the monuments when undertaking stabilization, conservation, or restoration projects intended to address such negative impacts.

Related posts:

The Ancient Site of Takhte Sulaiman

UNESCO: The Parthian Fortresses of Nysa

UNESCO: Sassanian Archaeological Landscape of the Fars Region

UNESCO: Citadel, Ancient City and Fortress Buildings of Derbent

Photos of the Atashgah (Zoroastrian Fire Temple) in Tbilisi, Georgia

Ancient Zoroastrian Temple discovered in Northern Turkey

Zoroastrian and Mithraic Sites of the Caucasus

Documentary Film Production: the UNESCO Sassanian Fortress in Darband

By Dr. Kaveh Farrokh|March 22nd, 2024|Archaeology, Architecture, Culture, Heritage, Military History 1900-Present, Mithraism, Mythology and Nowruz, Sassanians, UNESCO, Zoroastrianism|Comments Off

International Day of Conscience April 5

Promoting a Culture of Peace with Love and Conscience

Promoting a Culture of Peace with Love and Conscience

The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of humankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people.” Moreover, article 1 of the Declaration states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

The task of the United Nations to save future generations from the scourge of war requires transformation towards a culture of peace, which consists of values, attitudes and behaviours that reflect and inspire social interaction and sharing based on the principles of freedom, justice and democracy, all human rights, tolerance and solidarity, that reject violence and endeavour to prevent conflicts by tackling their root causes to solve problems through dialogue and negotiation and that guarantee the full exercise of all rights and the means to participate fully in the development process of their society.

Conscious of the need for the creation of conditions of stability and well-being and peaceful and friendly relations based on respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion, the General Assembly declared 5 April the International Day of Conscience.

The General Assembly invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations system and other international and regional organizations, as well as the private sector and civil society, including non-governmental organizations and individuals, to build the Culture of Peace with Love and Conscience in accordance with the culture and other appropriate circumstances or customs of their local, national and regional communities, including through quality education and public awareness-raising activities, thereby fostering sustainable development.

https://www.un.org/en/observances/conscience-day

History

The inaugural International Day of Conscience was first commemorated in 2020 by the United Nations General Assembly. This annual observance was established to encourage people around the world to introspect, follow their conscience, and do what is right.