VINDOLANDA, ENGLAND—A sandstone relief believed to represent Victoria, the Roman goddess of Victory, was unearthed from the Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, according to a statement released by the Vindolanda Trust. The deity was highly esteemed in Roman society, especially among soldiers, and was often honored after military success on the battlefield. The foot-and-a-half-tall sculpture was found in the rubble above a military barracks at the site, where as many as 800 Roman auxiliary troops were stationed. Archaeologists believe that it may have been part of an ornamental arch or gate that once adorned the building. The barracks and the relief likely date to the early third century a.d., a tumultuous time in Britain when Roman troops clashed with rebellious native tribes north of the wall in a conflict known as the Severan wars. The commission of a monument featuring the Victory goddess likely symbolized the end of that conflict and the building of new military infrastructure at Vindolanda. “Finds like this are increasingly rare these days from Roman Britain, but the beautifully carved figure vividly reminds us that Roman forts were not simply utilitarian, they had grandeur and of course the symbolism was a vital part of the culture here for the soldiers almost 2,000 years ago,” said archaeologist Andrew Birley. For more about discoveries at Vindolanda, go to “The Wall at the End of the Empire: Life on the Frontier.”

VINDOLANDA, ENGLAND—A sandstone relief believed to represent Victoria, the Roman goddess of Victory, was unearthed from the Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, according to a statement released by the Vindolanda Trust. The deity was highly esteemed in Roman society, especially among soldiers, and was often honored after military success on the battlefield. The foot-and-a-half-tall sculpture was found in the rubble above a military barracks at the site, where as many as 800 Roman auxiliary troops were stationed. Archaeologists believe that it may have been part of an ornamental arch or gate that once adorned the building. The barracks and the relief likely date to the early third century a.d., a tumultuous time in Britain when Roman troops clashed with rebellious native tribes north of the wall in a conflict known as the Severan wars. The commission of a monument featuring the Victory goddess likely symbolized the end of that conflict and the building of new military infrastructure at Vindolanda. “Finds like this are increasingly rare these days from Roman Britain, but the beautifully carved figure vividly reminds us that Roman forts were not simply utilitarian, they had grandeur and of course the symbolism was a vital part of the culture here for the soldiers almost 2,000 years ago,” said archaeologist Andrew Birley. For more about discoveries at Vindolanda, go to “The Wall at the End of the Empire: Life on the Frontier.”

Ancient Tomb Discovered High in Mountains of Peru

KUÉLAP, PERU—Colombia One reports that archaeologists made new discoveries at the site of Kuélap, high in the mountains of the country’s Amazonas region. Known for its massive stone walls, the settlement was founded 10,000 feet above sealevel in the sixth century a.d. by the mysterious Chachapoya civilization, sometimes referred to as the “Warriors of the Clouds.” In a newly investigated part of the site known as Research Area No. 1, a team from the Kuélap Archaeological Research Program explored six circular stone features arranged around a central courtyard. One of these contained an aboveground tomb known as a chulpa that is commonly found in the Andean highlands. The structure still held human remains and several finely crafted funerary objects, including a polished stone ax and a slate pendant etched with geometric patterns. Other artifacts included stone fragments and small traces of metal, which may have been used during farewell rituals before the site was abandoned around 1570, following the arrival of Spanish conquistadors. The discovery suggests that the burials were not random, but were organized with specific cultural traditions attached to them. The new findings could offer additional clues about how Chachapoya families and communities were organized. For more on the Chachapoyas, go to “Around the World: Peru.”

KUÉLAP, PERU—Colombia One reports that archaeologists made new discoveries at the site of Kuélap, high in the mountains of the country’s Amazonas region. Known for its massive stone walls, the settlement was founded 10,000 feet above sealevel in the sixth century a.d. by the mysterious Chachapoya civilization, sometimes referred to as the “Warriors of the Clouds.” In a newly investigated part of the site known as Research Area No. 1, a team from the Kuélap Archaeological Research Program explored six circular stone features arranged around a central courtyard. One of these contained an aboveground tomb known as a chulpa that is commonly found in the Andean highlands. The structure still held human remains and several finely crafted funerary objects, including a polished stone ax and a slate pendant etched with geometric patterns. Other artifacts included stone fragments and small traces of metal, which may have been used during farewell rituals before the site was abandoned around 1570, following the arrival of Spanish conquistadors. The discovery suggests that the burials were not random, but were organized with specific cultural traditions attached to them. The new findings could offer additional clues about how Chachapoya families and communities were organized. For more on the Chachapoyas, go to “Around the World: Peru.”

Pasargad Heritage Foundation’s open letter to US Congress members regarding President Trump’s statements and the Persian Gulf

Pasargad Heritage Foundation’s open letter to US Congress members regarding President Trump’s statements and the Persian Gulf

Pasargad Heritage Foundation’s open letter to US Congress members regarding President Trump’s statements and the Persian Gulf

Dear Honorable Members of the U.S. Congress

According to news outlets, President Trump will soon travel to Saudi Arabia and intends to change the historical name of the Persian Gulf—one of the world’s oldest recognized geographical areas and an intangible site of natural heritage for the Iranian people—to please his hosts.

We trust that the leadership of a knowledgeable nation such as the United States is well aware of the historical fact that the Persian Gulf has been identified on world maps for centuries as representative of Iran and its people. This is a historical reality that cannot be altered or conceded, even within the limited span of a four-year presidential term.

The current situation in Iran, a country under a government whose actions have resulted in the destruction of Persian historical sites and transfer of Iranian properties to enemies, causes significant distress and dismay for the Iranian people.

And now such statements made by President Trump can be particularly painful for those Iranians who have historically held the American people in high regard and considered them friends.

Sincerely,

Shokooh Mirzadegi

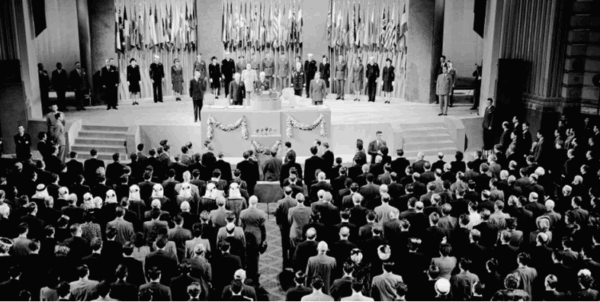

The historic event that established the conditions for the creation of the United Nations May 8 – 9

By resolution 59/26 of 22 November 2004, the UN General Assembly declared 8–9 May as a time of remembrance and reconciliation and, while recognizing that Member States may have individual days of victory, liberation and commemoration, invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations System, non-governmental organizations and individuals to observe annually either one or both of these days in an appropriate manner to pay tribute to all victims of the Second World War.

By resolution 59/26 of 22 November 2004, the UN General Assembly declared 8–9 May as a time of remembrance and reconciliation and, while recognizing that Member States may have individual days of victory, liberation and commemoration, invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations System, non-governmental organizations and individuals to observe annually either one or both of these days in an appropriate manner to pay tribute to all victims of the Second World War.

The Assembly stressed that this historic event established the conditions for the creation of the United Nations, designed to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, and called upon the Member States of the United Nations to unite their efforts in dealing with new challenges and threats, with the United Nations playing a central role, and to make every effort to settle all disputes by peaceful means in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations and in such a manner that international peace and security are not endangered.

On 2 March 2010, by resolution 64/257, By resolution 59/26 of 22 November 2004, the UN General Assembly declared 8–9 May as a time of remembrance and reconciliation and, while recognizing that Member States may have individual days of victory, liberation and commemoration, invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations System, non-governmental organizations and individuals to observe annually either one or both of these days in an appropriate manner to pay tribute to all victims of the Second World War.

The Assembly stressed that this historic event established the conditions for the creation of the United Nations, designed to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, and called upon the Member States of the United Nations to unite their efforts in dealing with new challenges and threats, with the United Nations playing a central role, and to make every effort to settle all disputes by peaceful means in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations and in such a manner that international peace and security are not endangered.

Background

On 2 March 2010, by resolution 64/257, the General Assembly invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations system, non-governmental organizations and individuals to observe 8-9 May in an appropriate manner to pay tribute to all victims of the Second World War. A special solemn meeting of the General Assembly in commemoration of all victims of the war was held in the second week of May 2010, marking the sixty-fifth anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

During the commemoration, the Secretary-General called the Second World War “one of the most epic struggles for freedom and liberation in history,” adding that “its cost was beyond calculation, beyond comprehension: 40 million civilians dead; 20 million soldiers, nearly half of those in the Soviet Union alone.”

In resolution 69/267, the General Assembly recalled that the Second World War “brought untold sorrow to humankind, particularly in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Pacific and other parts of the world.” It underlined “the progress made since the end of the Second World War in overcoming its legacy and promoting reconciliation, international and regional cooperation and democratic values, human rights and fundamental freedoms, in particular through the United Nations, and the establishment of regional and sub-regional organizations and other appropriate frameworks.”

A special solemn meeting, marking seventieth anniversary of the Second World War, was held on 5 May 2015.

General Assembly invited all Member States, organizations of the United Nations system, non-governmental organizations and individuals to observe 8-9 May in an appropriate manner to pay tribute to all victims of the Second World War. A special solemn meeting of the General Assembly in commemoration of all victims of the war was held in the second week of May 2010, marking the sixty-fifth anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

During the commemoration, the Secretary-General called the Second World War “one of the most epic struggles for freedom and liberation in history,” adding that “its cost was beyond calculation, beyond comprehension: 40 million civilians dead; 20 million soldiers, nearly half of those in the Soviet Union alone.”

In resolution 69/267, the General Assembly recalled that the Second World War “brought untold sorrow to humankind, particularly in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Pacific and other parts of the world.” It underlined “the progress made since the end of the Second World War in overcoming its legacy and promoting reconciliation, international and regional cooperation and democratic values, human rights and fundamental freedoms, in particular through the United Nations, and the establishment of regional and subregional organizations and other appropriate frameworks.”

A special solemn meeting, marking seventieth anniversary of the Second World War, was held on 5 May 2015.

Persepolis Architects Were Geologists as Well

The article “Persepolis Architects Were Geologists, too” was originally published in Mehr News on December 23, 2005 and by Shapur Suren-Pahlav in the CAIS venue on December 23, 2005.

=======================================================================================

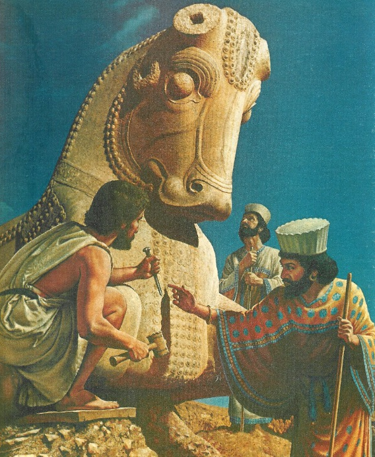

Recent geological studies at the Persepolis historical site indicate that Achaemenid dynastic era architects used their unique knowledge of geology and mines in the construction of Persepolis, as reported by the Persian service of CHN. The experts were well aware of the science of geology and were keen to discover underground sources of water, geologist Azam Zare said.

A Possible Qanat (or aqueduct water system) under Persepolis (Source: Sina Press).

A Possible Qanat (or aqueduct water system) under Persepolis (Source: Sina Press).

The studies show that the Achaemenid experts had acquired specialized knowledge and technology, but it is unclear how they mastered these skills, she added. The studies of the geological team at Persepolis led to the discovery of stone mines at mounts Rahmat and Majdabad and the Sivand Mine. As noted by Zare:

“Majdabad is far from Persepolis, but the Achaemenid experts used to travel all that distance to acquire the stones they needed. Several experiments carried out on the stones of the three regions by archaeologists show that the stones at Majdabad and Rahmat were of a better quality and were stronger compared with those of Sivand …”

Persepolis is located near Marvdasht in a region with large underground water reservoirs, and that is why the Achaemenids faced no problems in building palaces and gardens, she explained. Studies on the wells around Persepolis are continuing, and geologists seek to determine the connections between the wells in the region, she said, adding that some of the wells are still in use but others have run dry over the years.

Achaemenid Engineers and (Greek or Lydian) craftsmen at Persepolis 500s BCE (Source: Wisgoon).

Unfortunately, the construction techniques used by the Achaemenids were forgotten after Alexander’s invasion of Iran, she said in conclusion.

Related posts:

By Dr. Kaveh Farrokh|December 20th, 2023|Achaemenid Military History, Achaemenids, Ancient: Prehistory – 651 A.D., Archaeology, Architecture, Cultural and Endangered Sites, Engineering|Comments Off

Hidden medieval graffiti deciphered in room of Jesus’ Last Supper in Jerusalem

A team of researchers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) found dozens of hidden medieval inscriptions within the Cenacle in Jerusalem—long believed to be the location of the Last Supper.

A team of researchers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) found dozens of hidden medieval inscriptions within the Cenacle in Jerusalem—long believed to be the location of the Last Supper.

Hidden medieval graffiti deciphered in room of Jesus’ Last Supper in Jerusalem

The Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Sion. Credit: Heritage Conservation Jerusalem Pikiwiki Israel

With the help of advanced imaging techniques such as ultraviolet filters, Reflectance Transformation Imaging, and multispectral photography, the researchers captured nearly 30 inscriptions and nine drawings on the walls of the room. These marks were plastered over for centuries and rediscovered only in the 1990s when the room was being restored.

The findings, which were recently published in Liber Annuus, the yearbook of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, offer a glimpse into the lives of Christian pilgrims who visited the site between the 14th and 16th centuries.

Hidden medieval graffiti deciphered in room of Jesus’ Last Supper in Jerusalem

Carved Coat of Arms with the inscription “Altbach”. This image is almost identical to the coat of arms of the modern city of the same name in southern Germany. It appears to have been left by an unknown pilgrim from the local knightly family. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Among the discoveries is an Armenian inscription that reads “Christmas 1300.” It supports the controversial theory that Armenian King Het’um II could have reached Jerusalem after his army’s victory in the Battle of Wādī al-Khaznadār in Syria in 1299. The inscription, carved high on the wall in a style common among Armenian nobles, supports the king’s pilgrimage argument in history.

Hidden medieval graffiti deciphered in room of Jesus’ Last Supper in Jerusalem

Digitally remastered black-and-white multispectral image of the “Teuffenbach” coat of arms from Styria. Directly below, the half-erased date 14.. can be seen. To the right are two further inscriptions: the monumental Armenian Christmas inscription and a Serbian inscription “Akakius”. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Another inscription, written in Arabic, ends with the words “…ya al-Ḥalabīya.” Scholars believe that it was written by a Christian woman from Aleppo—based on the feminine grammatical form.

The Cenacle, located on Mount Sion, is sacred to Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Christians believe it to be the site of the Last Supper. Jews and Muslims consider it to be the tomb of King David. The current building was built during the Crusader period and once formed part of a Franciscan monastery before the Ottomans expelled the friars in 1517.

https://archaeologymag.com/2025/04/medieval-graffiti-in-room-of-last-supper/

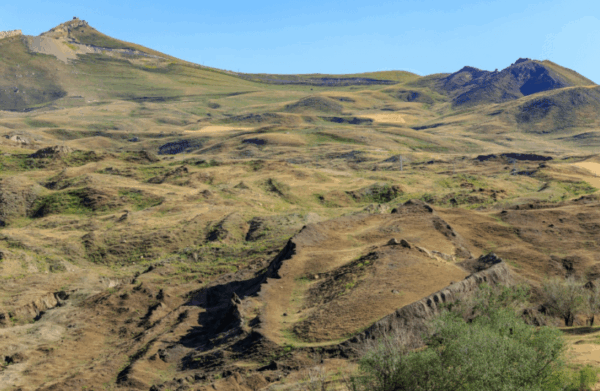

US team plans first dig at Mount Ararat’s ship-shaped hill

Ground-penetrating radar carried out by the group has revealed what members describe as “a rectangular structure” lying several metres below the surface.

Ground-penetrating radar carried out by the group has revealed what members describe as “a rectangular structure” lying several metres below the surface.

By JERUSALEM POST STAFFAPRIL 25, 2025 23:00

A California research collective known as Noah’s Ark Scan says it will begin the first controlled excavation of the Durupınar Site on Mount Ararat’s southern flank once a preservation framework is in place with local universities.

“After securing additional information in cooperation with local universities in Turkey, we will establish a site-preservation plan and confirm whether the structures discovered through radar scans are artificial or natural,” the team told the Korean outlet FN News.

Ground-penetrating radar carried out by the group has revealed what members describe as “a rectangular structure” lying several metres below the surface. The anomalous shape sits inside a flat, oval hill some 160 metres long—almost exactly the length assigned to Noah’s Ark in Genesis.

https://www.jpost.com/archaeology/archaeology-around-the-world/article-851490

Happy Persian Gulf Day

Iranians celebrate Persian Gulf Day on April 30th every year. The Persian Gulf is the name of an important waterway in Western Asia and the Middle East, located along the Sea of Oman and between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.

The Persian Gulf is the name of an important waterway in Western Asia and the Middle East, located along the Sea of Oman and between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.

Geologists believe that about five hundred thousand years ago, the first form of the Persian Gulf was formed next to the southern plains of Iran and over time, due to changes in the internal and external structure of the earth, it found its current stable form.

The historical name of this body of water has always been linked to the names of the Iranian territory and has been translated or equivalent to “Persian Gulf, Persian Sea and Persian Sea” in various languages. Also, in all international organizations, the official name is “Persian Gulf”

World Creativity and Innovation Day 21 April

World Creativity and Innovation Day – 21 April

World Creativity and Innovation Day – 21 April

Creativity and innovation in problem-solving

There may be no universal understanding of creativity. The concept is open to interpretation from artistic expression to problem-solving in the context of economic, social and sustainable development. Therefore, the United Nations designated 21 April as World Creativity and Innovation Day to raise awareness of the role of creativity and innovation in all aspects of human development.

Creativity shows who we are and what we value. It helps build a rich mix of cultures and supports social and economic growth. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), following the 2005 Convention helps countries strengthen their creative industries and promote artistic freedom.

Creativity and culture

The creative economy too has no single definition. It is an evolving concept which builds on the interplay between human creativity and ideas and intellectual property, knowledge and technology. Essentially it is the knowledge-based economic activities upon which the ‘creative industries’ are based.

Creative industries –which include audiovisual products, design, new media, performing arts, publishing and visual arts– are a highly transformative sector of the world economy in terms of income generation, job creation and export earnings. Culture is an essential component of sustainable development and represents a source of identity, innovation and creativity for the individual and community. At the same time, creativity and culture have a significant non-monetary value that contributes to inclusive social development, to dialogue and understanding between peoples. Today, the creative industries are among the most dynamic areas in the world economy providing new opportunities for developing countries to leapfrog into emerging high-growth areas of the world economy.

New momentum for the SDGs

On World Creativity and Innovation Day, the world is invited to embrace the idea that innovation is essential for harnessing the economic potential of nations. Innovation, creativity and mass entrepreneurship can provide new momentum towards achieving the Sustainable Sustainble Goals (SDGs). It can harness economic growth and job creation, while expanding opportunities for everyone, including women and youth. It can provide solutions to some of the most pressing problems such as poverty eradication and the elimination of hunger. Human creativity and innovation, at both the individual and group levels, have become the true wealth of nations in the twenty-first century.

International Day for Monuments and Sites 2025

International Day for Monuments and Sites 2025

Heritage under Threat from Disasters and Conflicts: Preparedness and Learning from 60 years of ICOMOS Actions

Heritage under Threat from Disasters and Conflicts: Preparedness and Learning from 60 years of ICOMOS Actions

At the 2023 General Assembly in Sydney, Disaster and Conflict Resilient Heritage – Preparedness, Response and Recovery was selected as the theme for the Triennial Scientific Plan (TSP) 2024-2027. The first year of the plan focuses on how we can prepare for possible disasters, through the prevention and mitigation of hazards, improving resilience, as well as by preparing for conflicts that threaten our cherished heritage resources.

In this context, one might ask in 2025: How can members and constituent Committees of ICOMOS better prepare for these disasters? What role can we play collectively, and what do we need to be effective in that work?

Following on from the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Venice Charter in 2024, ICOMOS will celebrate its 60th anniversary in 2025. The Second Congress of Architects and Specialists of Historic Buildings, held in Venice in 1964, adopted 13 resolutions, the first being the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites, better known as the Venice Charter, and the second, put forward by UNESCO, was the creation of ICOMOS in 1965.

The International Day for Monuments and Sites (IDMS), celebrated each year on 18 April, provides us with a unique opportunity to raise awareness of our organization and the work we do to conserve and protect the world’s universally significant cultural resources under threat of accelerating disasters and conflicts. The 2025 IDMS celebrations will therefore focus on the 60 years of ICOMOS actions in relation to safeguarding heritage under threat of disasters and conflicts as well as its future objectives in prevention, mitigation, preparation, emergency response, and recovery that we can take to safeguard heritage in times of crisis. The 2025 IDMS activities and recognition of our work over the last 60 years will conclude with the Symposium of the ICOMOS Annual General Assembly (Nepal, 13-19 October 2025).

While ICOMOS will celebrate the theme of Heritage under Threat of Disasters and Conflicts: Preparedness and Learning from 60 years of ICOMOS Actions non-ICOMOS organisations, institutions, NGOs are also invited to acknowledge the IDMS under the overarching theme of Disaster and Conflict Resilient Heritage and are encouraged to share their experiences, events, publications and outcomes of discussions with ICOMOS members and the International Secretariat. This collaboration will help to raise awareness and assist in the identification of the wide range of scientific and traditional practices worldwide that contribute to the protection of heritage in extreme and extraordinary circumstances.

Get involved!

ICOMOS members and heritage professionals are welcome to (i) consider the potential impacts on heritage resources by conflict and disaster; (ii) examine what resilience looks like in the face of those impacts; (iii) and what one can do to PREPARE from your national and scientific perspectives. This involves the examination of previous actions undertaken by ICOMOS committees since 1965; and future actions ICOMOS members and others in our communities can consider in the protection of heritage against disasters and conflicts.

Some of the activities might include inventorying, collecting data on damage and losses and assessment of vulnerabilities; understanding risks and building corresponding capacities; collaboration between stakeholders; communication between relevant agencies in the heritage and disaster risk management sectors; traditional knowledge on disaster risk mitigation and preparedness; inventorying successful practices and examples in preparedness.

ICOMOS Committees are called upon to organise and collaborate on events on the theme of PREPAREDNESS of resilient heritage in the face of conflict and disaster by considering ICOMOS Actions over the last 60 years.

Members can share their events with ICOMOS by writing to: communication[at]icomos.org

Potential formats for participation can include, but are not limited to:

1 to 2 minutes (maximum) video submissions from each ICOMOS National Committee, International Scientific Committee, Working Groups and individual members, showcasing local and regional approaches to caring for heritage in advance of conflicts and disasters. The videos may be shared with communication[at]icomos.org. Make sure to include descriptions, quotes or facts to accompany any video, as well as hashtags.

Photographic submission with credits and captions to explain current conservation practice approaches, changing narratives and goals for the future of cultural heritage, to adapt to the urgent demands of PREPAREDNESS in the face of conflict and disaster. In all cases, please make sure that you retain the rights to any image you share.

Organise virtual roundtables, host webinars, propose workshops to reflect on the

https://www.icomos.org/actualite/international-day-for-monuments-and-sites-2025-heritage-under-threat-from-disasters-and-conflicts-preparedness-and-learning-from-60-years-of-icomos-actions/