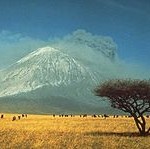

The world’s second-largest national park is under threat from a destructive combination of climate change, oil and gas development and hydroelectric projects, according to a new report

The world’s second-largest national park is under threat from a destructive combination of climate change, oil and gas development and hydroelectric projects, according to a new report

from the Canadian government and published by a number of news outlets.

Wood Buffalo national park, which spans Alberta and the Northwest Territories, was placed on

UNESCO’s endangered list in 2017, and Canadian authorities were given one year to develop a solution to stem the rapid deterioration of the park. The UNESCO had warned that inaction would “constitute a case for recommending inscription of Wood Buffalo national park on the list of World Heritage in Danger” as reported by the Guardian.

In June this year (June 2018), ahead of the UNESCO meeting in Bahrain, the Canadian

government’s report confirmed that the problems are only getting worse. The extensive 4.5m hectare park has long been a home to the Cree and Dene indigenous peoples and it is also habitat for the largest free-roaming buffalo population in the world.

Wood Buffalo – which became a world heritage site in 1983 – includes part of the world’s largest boreal river delta, formed by the Peace and the Athabasca rivers, which both run through the park and create the conditions for an extremely diverse ecosystem. It has been reported that in 2014, the Miskew Cree First Nation contacted UNESCO over fears the ecosystem was rapidly deteriorating. According to the Guardian, the community members no longer drink the fresh water from lakes or streams over fears of contamination and have reported that wild fish and game have developed abnormal flavors and deformities. While there is no clear explanation of

what has caused problems in the food sources, the Canadian government’s environmental assessment report says high levels of mercury have been found in fish and bird eggs.

In 2016 a study by UNESCO researchers warned that the pace and complexity of industrial development around the park was “exceptional” and found the proper mechanisms to adequately study its impacts were absent. The report also found that “the long-term future of the property’s two most iconic species, wood bison and whooping crane, remains uncertain and requires permanent attention” according to the Guardian newspaper. A 2017 another report by UNESCO and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature determined the problems facing Wood Buffalo were “far more complex and severe than previously thought”.

In addition, the new oil and gas operations in the northern reaches of Alberta continue to draw large amounts of water to sustain their operations. “Seasonal flows in the Athabasca River have declined over the past 50 years due to a combination of increased water withdrawals and (past) climate change,” said the Canadian government’s report. Experts on the UN committee also fear increased development in the region –including recently approved mining permits – creates near-unavoidable risks of chemical spills into the water system.

While Canada is trying to respond to the 2017 request of the World Heritage Committee to develop an action plan for the site, and is taking concrete steps to address the recommendations of the recent reactive monitoring mission to Wood Buffalo national park as the Canadian government has stated, environmentalists however, believe that by the time real actions could be taken, it will be too late for one of the most beautiful national parks in the world and a UNESCO Heritage Site.