SOAS University of London was the venue for the world premiere screening of the film Taq Kasra: Wonder of Architecture (see the preview here), directed by documentary film-maker Pejman Akbarzadeh.

SOAS University of London was the venue for the world premiere screening of the film Taq Kasra: Wonder of Architecture (see the preview here), directed by documentary film-maker Pejman Akbarzadeh.

The premiere was attended by more than 150 people, including international students, scholars and members of the Persian and Iraqi communities in London.

The film was produced by the Persian Dutch Network in association with Toos Foundation, and was funded by the Soudavar Memorial Foundation.

Taq Kasra

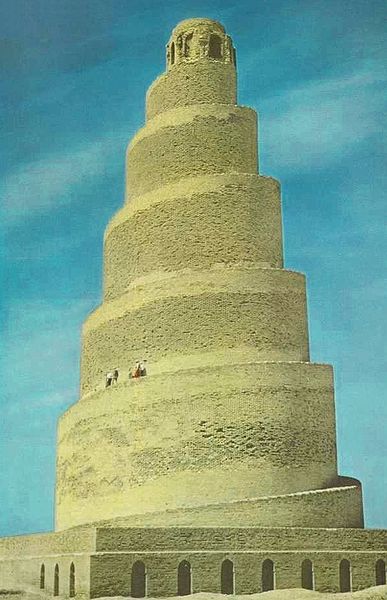

Taq Kasra is the only visible remaining structure of the ancient Persian city of Ctesiphon. Once part of a much bigger palace, Taq Kasra remains the largest single-span brick vault in the world and, as such, is an object of great architectural and historical importance.

The palace was once the symbol of the Persian Empire in the Sasanian era (224-651 AD). Nowadays, the remains of the site are located in modern-day Iraq, approximately 25 miles southeast of Baghdad.

Pejman Akbarzadeh

Pejman Akbarzadeh’s first documentary film Hayedeh: Legendary Persian Diva was nominated ‘best documentary’ at the Noor Iranian Film Festival in Los Angeles.

Taq Kasra: Wonder of Architecture is his second film.

Here Pejman answers questions about the project.

What fostered your own personal interest in Taq Kasra?

“I am originally from Persia so, in general, I am interested in ancient Persian monuments, but in regard of Taq Kasra the story was different. It is a Persian monument, but now it is no longer on Persian soil. It is located in Iraq, a country, which has experienced war and violation since the early 1980s. Even before that date, Iraq’s relationship with Persia (Iran) was not very friendly, so very few people from Iran dared to go there to visit the arch. And now almost no one!

“During the recent conflict with ISIS in Iraq, I was shocked watching the footage of ISIS attacks to historical monuments and museums in northern Iraq. Some years beforehand, the Taliban did the same thing to various sites in Afghanistan. During the Battle of Fallujah in 2016, ISIS came quite close to Taq Kasra, around 60 kms away. So, it became a nightmare for me thinking that a similar attack might happen to this monument as well. I told myself I had to go there and film the arch from various angles before it is destroyed. I could not prevent ISIS, but I could document the arch before destruction. However, fortunately, the Iraqi army defeated ISIS in Fallujah before any destruction occurred.”

The attacks on Nimrud and the destruction of the Great Mosque of Al-nuri in Mosel hit the Western media headlines. Can you quantify what else has been lost?

“I think the Western media coverage was fantastic. Before that, people knew very little about cultural heritage in Iraq, which is related to ancient Mesopotamia. But reports about the attacks to the historical monuments in northern Iraq, and also museums being looted, informed the public about the situation in the country and its rich cultural heritage. Currently – as far as I know – various organisations from Europe and the United States are cooperating with Iraqis to restore the sites and museums. A few months ago, a team of Iraqi archaeologists were in London for an intensive training course at the British Museum, and also there is a UK-based charity for the restoration of Basra Museum. There is an ongoing campaign to find looted artefacts of the National Museum as well.”

It must have been hard getting permission to film in Iraq. What difficulties did you face?

“One of the biggest problems working in Iraq is that it is very difficult to find out which organisation is responsible for what, and also inside Iraq various organisations interfere in each other’s areas. In December 2016, when I travelled to Iraq for the first time, even though I had a valid Press Visa from the Embassy of Iraq in The Hague and also permission for filming from ‘CMC’, my equipment was confiscated upon my arrival at Baghdad Airport. I noticed that some other journalists from Western countries had the same problems.”

“I returned to Amsterdam without having been able to film even one second of film.”

“But later I was lucky enough to be introduced to Qahtan Al-Abeed, the director of Basra Museum in southern Iraq. He advised me to enter Iraq through Basra, which is much safer than Baghdad, and from there travel to the Ctesiphon area by car, to film the arch. It was because of Qahtan’s cooperation that I was able to finish the project.”

Did you use a drone camera to obtain the footage of Taq Kasra from above?

“Yes. Getting permission to use a drone was very difficult, because ISIS started to drop bombs in Iraq via drones. But I convinced the Iraqi authorities that I was going to use it just to film Taq Kasra, which is located 35 kms outside Baghdad. However, the area (Salman Pak) was/is not safe, and after around 30 minutes, I was told that I had to leave.”

There are intentions to restore Taq Kasra by the current Iraqi Government. Do you see a more stable future for the site?

“In general, Iraqi officials are becoming more active trying to protect the historical monuments and sites in their country. Particularly after the ISIS attacks to the monuments and also the looting of the Iraqi National Museum in Baghdad, I feel they are paying more attention to such issues. In recent years, the Iraqi Ministry of Culture has invited a Czech firm to restore Taq Kasra but I am a little bit surprised why they have assigned this Czech firm. Taq Kasra is an ancient monument and there are Italian teams with more experience of similar missions.”

As reported on: https://www.soas.ac.uk/blogs/study/taq-kasra/