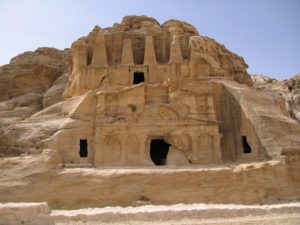

The infrastructure of Petra, the capital of the ancient Nabateans, still remains a mystery to most people who visit this heritage site. The focus of tourists when they arrive to Petra is to find splendid monuments, temples, shrines, churches and market places, but the water infrastructure and the way Nabateans preserved water for irrigation and drinking is relatively unknown, noted Ulrich Bellwald, a Swiss archaeologist, conservator and architect.

Surveys of Siq Al Mudhlim,Wadi Mataha, Khazne Plaza and the Outer Siq with hydraulic and archaeological research programmes gave further results regarding the water supply system and the flash flood prevention system, Bellwald said.

Based on these results, the survey of the entire Petra area was elaborated and all the visible remains of the city’s hydraulic system were recorded and documented, the scholar continued.

Moreover, a first relative chronology could be established, showing how the entire system was developed over the centuries, how it declined and finally collapsed, he said, underlining that “for each single element of the system, its function in the entire network and its technical and constructive characteristics could be determined”.

During early phases of the city development in the 1st century BC, Bellwald said, the Nabateans collected run-off water in cisterns located on roofs of buildings and surrounding areas.

One of these early cisterns was excavated by a team from Basel University below the mansion at Zhantur IV, the scholar stated, noting that it dates to the first half of the 1st century BC and was then “overbuilt by the foundations of the walls belonging to the construction from the very beginning of the 1st century AD”.

“The pottery found in the retention basin of the dam number 3 in Wadi Al Jarra corresponds perfectly with the results from all my other excavations connected with the hydraulic infrastructure, in the Siq and in Wadi Al Madrass,” said the expert and author of the book ” The Petra Siq: Nabatean hydrology uncovered”, adding that the oldest shards are from the mid 1st century BC, the main amount from the last quarter of the 1st century BC and the finds stopped around 80 AD.

“Also, the French excavations in the Obodas chapel have given the same results, which proves that the entire hydraulic system, that is the aqueducts for the drinking water supply and the flash flood retention system, have been planned in the mid-1st century BC and then realised between 50 and 25 BC, and they were fully operational in the last quarter of the 1st century BC,” Bellwald noted.

The excavations in the Siq revealed sections of an underground gravity flow channel that followed the surface of the trampling path before the construction of the paved road, the expert said, explaining that “the channel was covered over its entire length and crossed wider faults on dams or even arched bridges”.

The sections excavated in the Siq and in the vicinity of the Temenos Gate by Professor Stephan Schmid showed exactly the same type of construction and interior plaster, Bellwald underlined.

“As due to the modern building activity in the town of Wadi Musa, no remains of this first channel have yet been discovered between Bab Al Siq area and the springs to the east of the city, so the original feeder of the aqueduct may not be determined.”

“But, based on the wide cross section of the channel, it must have been a spring with a great capacity, hence it was most probably Ain Musa,” the expert speculated.

The sections of this first gravity flow channel excavated in the Siq have shown that this first aqueduct must have been destroyed by a flash flood in the middle of the 1st century BC, Bellwald explained.

Furthermore, the constructive characteristics of the first spring water channel, as revealed by the excavated sections in the Siq and near the Temenos Gate, and by the still visible remains in the Bab Al Siq area are clearly showing that this first aqueduct was built as a completely hidden, underground construction, which was a common way to do in Greece from archaic period and consequently implemented in the Hellenistic cities in Asia Minor like Pergamon, emphasised the Swiss scholar.

On the other hand, the Khubtha north aqueduct represents the first spring water aqueduct to be completely visible above the ground, the architect said, replacing the older destroyed channel in the Siq.

Petra has five aqueducts: Khubtha, Siq, Ain Braq, Ain Abu Olleqa and Ain Debdehbeh, with an overall length of 55,263 metres.

After the earthquake of 363AD, most of these Hellenistic aqueducts were destroyed and never reconstructed, so the city installed other water systems in order to provide water to its population, according to Bellwald.

“Only the gravity flow channel in the Siq was repaired during the Byzantine rule and prolonged into the city centre,” he said, adding that it was “clearly related to the Byzantine level of the paved street, which was several metres above the Nabataean pavement”.

The significantly-reduced population of Petra returned to run-off water collection systems as “may be shown by the cistern in the courtyard in front of the Petra Church”, the scholar noted.

“At its final stage, the spring water supply system of Petra covered the entire area of the city basin, bringing spring water from the east, south and north into the city. The location of the end reservoirs shows that all four quarters of the city had their own aqueduct,” Bellwald concluded.