The Persian Prince Pirouz (Pirooz)

By Dr. Kaveh Farrokh

The article “The Persian prince Pirooz“ by Yang Guifei was originally printed in the Tang Dynasty Times. Kindly note that excepting one image, none of the other images, video and accompanying descriptions appear in the version printed below. For more on the Sassanians consult:

The Sassanians (224-651 CE)

Military History and Armies of the Sassanians

===================================================================

Sometime around the year 670, a shining prince — Pirouz (or Pirooz) the son of the last Sassanid King — arrived in the Tang capital. He was there to beg for protection from the Arab invaders who now occupied his country. Exhausted and covered in dust from the journey, the young prince– who was barely out of boyhood–was led into the Great Hall. It had taken him the best part of a decade to arrive. In fact, he never believed he would actually make it; imagining instead being murdered or perhaps dying from cold and exhaustion somewhere en route over the towering mountains and terrifying deserts through which he had passed on his way East.

A rectangular piece of tapestry coming from the Xingjian Ughur Autonomous Region of China clearly showing Sasanian Persian influences in design and artwork. The physiognomy of the person drawn in the tapestry is Caucasoid as opposed to Asiatic, indicative of the strong Indo-European presence in the region since proto Indo-Europeans (i.e. the Tocharians) first entered the region thousands of years ago (Picture source: Houston Museum of Natural Science). Several Western researchers however suggest that the person depicted above is a Greek.

A rectangular piece of tapestry coming from the Xingjian Ughur Autonomous Region of China clearly showing Sasanian Persian influences in design and artwork. The physiognomy of the person drawn in the tapestry is Caucasoid as opposed to Asiatic, indicative of the strong Indo-European presence in the region since proto Indo-Europeans (i.e. the Tocharians) first entered the region thousands of years ago (Picture source: Houston Museum of Natural Science). Several Western researchers however suggest that the person depicted above is a Greek.

Somehow, though, he did make it, and arriving at dusk, just before the gates of the great city were secured shut for the night, a regiment of guards from the Chinese Emperor’s Palace arrived to escort him through the city.

And what a city it was.

When he was a child, his father had told him much about the great capital to the East– larger and richer than even Rome or Byzantium. Rome, of course, had been sacked two centuries before, and Byzantium was itself in decline. And then there was his own glorious empire– it still brought tears to his eyes just thinking of it. The Sassanid Empire had been the greatest empire on earth– rivaled only by Byzantium to the West and China to the East, but it now lay in ruins. His family all dead, his heritage scattered like the sands of the desert blown here and there in the wind.

Fresco along the Tarim Basin, China depicting an Iranian-speaking Buddhist monk (Kushan, Soghdian, Persian or Tocharian?) [at left] instructing a Chinese monk [at right] on philosophy (c. 9th-10th Century). Iranian peoples of Central Asia were the link between Asia as a whole and the civilizations of ancient Iran, notably Sassanian and post-Sassanian culture(s). Open and tolerant, the Soghdians, Kushans, Tocharians, etc. established a sophisticated literature and urban culture (Lecture slide from Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures from the course “The Silk Route: origins & History“).

Fresco along the Tarim Basin, China depicting an Iranian-speaking Buddhist monk (Kushan, Soghdian, Persian or Tocharian?) [at left] instructing a Chinese monk [at right] on philosophy (c. 9th-10th Century). Iranian peoples of Central Asia were the link between Asia as a whole and the civilizations of ancient Iran, notably Sassanian and post-Sassanian culture(s). Open and tolerant, the Soghdians, Kushans, Tocharians, etc. established a sophisticated literature and urban culture (Lecture slide from Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures from the course “The Silk Route: origins & History“).

When the Arabs had invaded, he and his family– along with a great entourage of supporters– had fled eastward. Born in 226 a.d. the ancient Persian Sassanid Empire had once stretched from the Levant and Constantinople in the West to the Indian subcontinent in the East and had encompassed all of present-day Iraq, Armenia and Afghanistan; as well as much of Turkey, Syria, Arabia and Pakistan. These lands– as well as the Persian colonies in Central Asia– were all part of the great Persian sphere of influence; whose emperors were held as equals by both the Roman and the Chinese emperors.

Chinese Admiral Zheng He who was of Persian descent. Zheng He is recognized for having sailed with his giant fleet to Europe and Africa. (Source: Chris Heller/CORBIS & The Mail).

For 400 years, they had been called Shahanshah– or, the “King of Kings.” And, theirs was the last great Persian empire prior to the invasion of the Arabs and the beginnings of Islam. Zororastrians by religion, it was a Kingdom ruled by a federation of aristocratic families whose splendid cultural achievements would be taken up by their Arab conquerors with gusto. In fact, much of what later came to be known as Islamic culture– from calligraphy and poetry to garden design and architecture– was borrowed largely from the Sassanian empire.

Tang dynasty depiction of foreign merchant in northern China, (7th century CE) housed at Paris’ Musee Guimet (Source: Per Honor et Gloria in Public Domain).

Tang dynasty depiction of foreign merchant in northern China, (7th century CE) housed at Paris’ Musee Guimet (Source: Per Honor et Gloria in Public Domain).

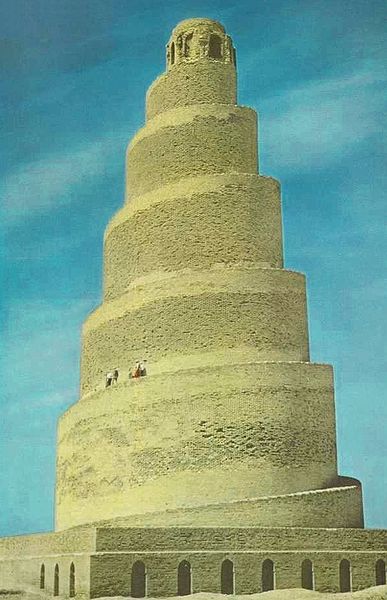

When the Arab conquerers stormed the Persian capital of Ctesiphon in 637, such were their numbers that his Father’s only choice had been to flee. From Ctesiphon, located on the Tigris, just a bit downstream from Baghdad (founded about 150 years later), on horseback they had raced East in the hope of gathering support for their cause. None of the great families, however, had agreed to help them mount an army to oust the Arab invaders, and by the time they had reached Merv, on the Eastern edge of their empire, they were spent.

Tse-Niao (Bird) motif mural painting in Kizil, Sinkiang, 6-7th Centuries AD. (left) and a Pheasant as depicted in late Sassanian arts 6-7th Centuries CE (Slide and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

Tse-Niao (Bird) motif mural painting in Kizil, Sinkiang, 6-7th Centuries AD. (left) and a Pheasant as depicted in late Sassanian arts 6-7th Centuries CE (Slide and caption from Kaveh Farrokh’’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

It was there that the greatest tragedy of all happened. His Father had been murdered– right in front of his own eyes. And what had been perhaps the greatest blow was that he had been murdered by a commoner. Robbed and murdered for his purse, the great Shahanshah, Yazdgerd III, had been killed by a miller. It was 651, and they had been in flight for some 14 years.

So, that had been that. With their cause now dead, the aristocratic and ruling families who had followed them East decided to stay and put down roots in Merv, as well as in the nearby Persian areas of Sogdiana, Tashkent and Khotan. Our young Prince, however, would always live with a price on his head. He, therefore, required protection. He thought and thought, but there seemed nowhere to turn– until he remembered his sister. Before he was born, she had already been married off to the great Tang Emperor to the East. And, so he had set out East–to China.

It was the heyday of the Silk Road, so he had just followed the well-worn path of other Persians before him. First into Sogdiana and then crossing the Pamirs, he had had to make it across the unending stretch of sand of the deserts of inner Asia. Skirting the southern edges of the Taklamakan Desert, first he traveled to Kashgar; then on to Yarkand, Khotan, and all the way to Dunhuang. From there, it had just been a matter of descending down off the plateau and heading East, toward the capital.

Chinese girls of ancient Iranian descent (Source:Iranian People Of China (中国的伊朗人)).

Chinese girls of ancient Iranian descent (Source:Iranian People Of China (中国的伊朗人)).

Persian peoples dominated the entire route. The great middle men of the Silk Road, Persian communities (and most notably the Sogdians) had greeted him in every town he passed through along the way. From Merv to Chang’an, whenever he stopped, he had stayed in Persian inns, eaten Persian foods and had spoken in the refined Persian language of the Court– and he was, for the most part– understood.

He would be further stunned to see of his country’s influence in China proper as well. It gave him heart. Yes, theirs had been the greatest civilization of the world– for even the Chinese thought so.

The Chinese capital, though, he had to admit, had surpassed even the Persian capital during its height. As French scholar Michel Beurdeley has noted, “the title of Middle Kingdom was richly deserved by China during the Tang dynasty,” as the high civilization and celebrated cosmopolitanism of the Tang dynasty truly had no precedent anywhere on earth prior to that time– not even Byzantium saw such a rich display of goods and peoples.

The above figure is from a Tang dynasty burial site, now housed now at the museum at Turin, Italy. Curators and scholars continue to debate the figure’s origins; one possibility is that he was of Iranian descent (Picture source: The Wall Street Journal).

The above figure is from a Tang dynasty burial site, now housed now at the museum at Turin, Italy. Curators and scholars continue to debate the figure’s origins; one possibility is that he was of Iranian descent (Picture source: The Wall Street Journal).

While the Tang capital of Chang’an was the largest, most international city in the world of the time, the Second Capital of Loyang was no less impressive. Both cities were inhabited by traders, entertainers and religious teachers and students from places as far-flung as Syria, Oman, Iran, Khotan, Sogdiana, Turkestan, Tibet, India, Champa, Funan, Korea, and Japan, just to name a few. There were Mosques, Jewish, Manichean and Zoroastrian temples, Nestorian churches, as well as Buddhist monasteries of all sects, some of which were great centers of scholarship. Most surprising (considering the inward turn China would take in the coming centuries) was how stunningly exotic and open the city was.

It was a city where wealthy ladies adorned their cheeks with crimson laq from Vietnam and anointed their bodies with perfumed oils of Cambodia; where aristocrats kept falcons from Korea, parrots from the jungles of Java and lapdogs from Samarkand. Sleeping in Turkish felt tents was the latest fashion as were the dance moves from Sogdiana. And, the music. The capital saw glorious performances by dancers from Central Asia and India showing dances of such beauty that the famed Tang poets of the time composed poem after poem about them. Grape wine had also come into fashion and was served in glass ewers from Persia. There were lychees from Canton and those oh-so famous peaches of Samarkand.

Iranian-speaking Tajik women from China. These are mainly clustered in the Karakorum region.

Iranian-speaking Tajik women from China. These are mainly clustered in the Karakorum region.

Of all the foreign fashions, the influence of Iran was without a doubt most significant of all. During the Tang, anything Persian– from music and dancing, to clothes, hairstyles and the game of Polo– enjoyed huge popularity at Court and among the aristocracy– indeed, they were considered to be the very height of fashion. This surprising turn in history came about as part of the Tang Dynasty’s political and military incursions further and further West, into Central Asia (to the land of their prized “blood sweating” stallions and jade) as well as into the Middle East (where beautiful glass and the mineral cobalt was secured).

It was the Iranian Sogdian peoples who held the greatest influence. They were the great merchants, traders and entertainers of the legendary silk road. Known in Chinese as hu jen 胡人, their cultural influence among the Chinese aristocrats was remarkable. It is written in the Tang histories that “the food of the aristocrats was hu food, their music hu music, and their women clothed in the most exotic hu robes that money could buy.” Indeed, in the words of one Japanese scholar, the Tang capital of Chang’an was “painted entirely in the colors of hu.”

https://youtu.be/lTuzU5M5Dh0?t=212

Video by Kings & Generals on the history of the last Sassanians and their anti-Caliphate alliance with the Tang dynasty of China (Source: Kings & Generals in YouTube).

And so our Persian Prince was pleasantly surprised. Such was the Chinese Emperor’s great appreciation of the accomplishments of the Persian civilization that upon their first meeting they declared themselves brothers. Born and raised the song of a King, the Prince knew not to make eye-contact with the Son of Heaven, and instead fell to his knees. The great Emperor rose to his feet and stepping off his dais, he bent down to bid the young Prince to his feet.

“You’ve come a long way. Have no more fears. For you are my brother and this is your new home.”

Prince Pirooz was to spend the rest of his days within China. He is said to have learned Kung Fu and then went on to become a general in the army. Sent West to fight their mutual enemies the Arabs, the Persian Prince used his remaining money and resources to make whatever trouble he could. He had probably given up all hope of re-taking his empire– still it must have felt good to win a battle or two. The Tang chronicles state that when the Chinese emperor died, Pirooz and his son Narseh were allowed to be stationed along the western border garrisons by the new Chinese emperor. Immediately, they started clashes against the Umayyad Arabs. Soliciting the aid of Turkish tribes, Prince Pirooz spent the rest of his days fighting the Arabs along China’s Western corridor.

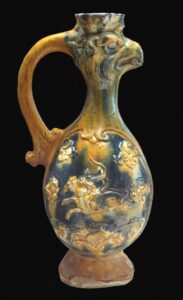

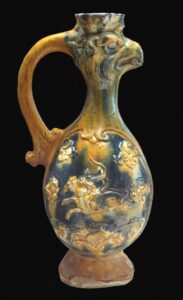

A well-preserved Tang vase (8-9th century CE) housed at the Guimet Museum. This bears distinct Sassanian artistic influences.

A well-preserved Tang vase (8-9th century CE) housed at the Guimet Museum. This bears distinct Sassanian artistic influences.

He died around 700 in the West, still fighting the Arabs wherever he could. His son– who also became a respected general in the Chinese army, wrote this in his diary (from Frank Wong’s article which is pretty much the only thing around online about Prince Pirooz):

Pirooz requested only a simple burial and the Chinese emperor approved. The entire exiled court was in attendance along with the Chinese emperor. The Chinese emperor held Pirooz’s shaking hands. Pirooz looked west and said: “I have done what I could for my homeland (Persia) and I have no regrets.” Then, he looked east and said: “I am grateful to China, my new homeland.” Then he looked at his immediate family and all the Persians in attendance and said: “Contribute your talents and devote it to the emperor. We are no longer Persians. We are now Chinese.” Then, he died peacefully. A beautiful horse was made to gallop around his coffin 33 times before burial, because this was the number of military victories he had during his lifetime. Pirooz was a great Chinese general and great Persian prince devoted and loyal to his people.

And so our Prince died in one of the most remote regions on earth; fighting his enemies till the very end. He was buried facing West.

There is a tomb and statue in China which bears this inscription: Pirouz, Shah of Iran, crowned in Tang dynasty court: Commander-in-chief of Iranian Army, Martial General of the Right [Flank] Guards, Awe-inspiring General of the Left [Flank] Guards. Peroz asked for Chinese military assistance in 661 CE against the Arabs occupying Iran. Pirouz’s descendants in China adopted the Tang dynasty’s Imperial Family Name of Li. Visitors to the tomb of Emperor Gaozong (r. 649-683 CE) and Empress Wu Zetian of the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) will see that one of the statues guarding the emperor as depicted above has the name of Sassanian prince Pirouz (d. 679 CE) as seen above (Picture source: 猫猫的日记本 in Public Domain). The statue had typical Iranian features, complete with long curly hair and the Parthian style mustache making it likely that this is either Pirouz himself or possibly his son Narseh. Pirouz was crowned in China after the Arab invasion which toppled the Sassanian Empire in 637-651 CE.

There is a tomb and statue in China which bears this inscription: Pirouz, Shah of Iran, crowned in Tang dynasty court: Commander-in-chief of Iranian Army, Martial General of the Right [Flank] Guards, Awe-inspiring General of the Left [Flank] Guards. Peroz asked for Chinese military assistance in 661 CE against the Arabs occupying Iran. Pirouz’s descendants in China adopted the Tang dynasty’s Imperial Family Name of Li. Visitors to the tomb of Emperor Gaozong (r. 649-683 CE) and Empress Wu Zetian of the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) will see that one of the statues guarding the emperor as depicted above has the name of Sassanian prince Pirouz (d. 679 CE) as seen above (Picture source: 猫猫的日记本 in Public Domain). The statue had typical Iranian features, complete with long curly hair and the Parthian style mustache making it likely that this is either Pirouz himself or possibly his son Narseh. Pirouz was crowned in China after the Arab invasion which toppled the Sassanian Empire in 637-651 CE.

One of Iran’s great contemporary playwrights, Bahram Beyzaie, wrote a very popular play about the murder of the last Sassanian King (Pirouz’s father) called the Death of Yazdgard. Put on just after the Revolution in Iran, it was not well-received by the authorities. Still it was made into a film and has been staged several times outside Iran (as recently as 2006, in fact). The play, which is compared to in significance to that of A Streetcar Named Desire or Death of a Salesman, basically explores issues of invasion (on many levels) and good kingship. This article about the Darvag performance in Berkeley and San Francisco is really interesting, especially about how they had to purge the play for any references about the ancient Arab invasion, because “we didn’t want to cause any misunderstandings — especially after 9-11.“

Related posts:

Pirooz in China: Defeated Persian army takes Refuge

The 1,500-Year-Old Love Story Between a Persian Prince and a Korean Princess that Could Rewrite History

Impact of Iranian Culture On East Asia

Pearls of the Taklamakan

Matteo Compareti: The last Sassanians in China

Dr. Masato Tojo: Zen Buddhism and Persian Culture

An Overview of Iranians in Japan during Earlier Times

Chinese-Iranian Relations in Pre-Islamic Times

The Plurality of the Persian Empire: The Achaemenids to the Sassanians

Marco Polo and the Persian Gulf

By Dr. Kaveh Farrokh|January 3rd, 2024|Central Asia, Culture, Heritage, India and Asia, Iran and Central Asia, Iran and China, Sassanians|Comments Off

Hundreds of Roman-era medical instruments now being examined by scientists may come from one of the earliest known examples of a group medical practice, or at least a place where health care workers congregated to treat people.

Hundreds of Roman-era medical instruments now being examined by scientists may come from one of the earliest known examples of a group medical practice, or at least a place where health care workers congregated to treat people.